Print or download fully-formatted pdf version here.

Chapter Outline

- The Examined Life

- The Life We Examine

- Contexts and Qualities

- Relationships

- Sources

- Forces

- The Currently Constructed Self

- Practices

- Triggers and Seeds

- Change

- The Examination of Life

- Using the Skills of Wisdom

- The Philosopher and the World

- The Depth Dimension

- Level One

- Level Two

- Level Three

- Level Four

- The Examined Life

- Dis-Integration-Driven and Ongoing Examination

- The Philosopher

- Reading: An Example from Epicurus

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter we will explore more deeply what philosophy (the love of wisdom) means. In particular we will explore philosophy as an examined life. After hearing again from Socrates, you will spend some time thinking about life: what is involved in the life we experience and how we develop the values and practices of life that we do. You will look more particularly at three parts (head, heart, hand) as they are integrated into our lives at different levels of depth. Then you will consider what it means to examine that life. You will explore one concrete example of this kind of examination of life in the writings of Epicurus, an ancient Western philosopher. And you will examine our expressions of our integrated lives as “models” of life. Finally, in the journal assignment you will have a chance to start examining your own life.

————————

Let’s begin with Plato and Socrates. If you remember, Plato was an ancient Greek philosopher who wrote “dialogues” between people as a way of communicating his reflections on the larger issues of life. The hero in most of Plato’s dialogues is Socrates, his mentor. Socrates was an influential teacher in Athens, though it appears he remained on the fringes of public life. He attracted many aristocratic young men as followers, who spread his views throughout the land. Socrates was so influential that today we divide ancient philosophy into (a) “Presocratic” philosophy and (b) the philosophy that comes after Socrates. When he was about seventy years of age, Socrates was convicted by the Athenian government of “corrupting the minds of the young” and of “honoring gods of his own invention rather than the gods recognized by the state.” He was sentenced to die by drinking poison hemlock. Plato’s Phaedo gives an account of the last hours of Socrates’ life. In the Apology (also translated “Defence”) Plato records Socrates’ speech to his fellow citizens as he is brought to trial. Here Socrates gives an account of his own convictions about things and about the way he has lived. It is a powerful testimony to the life of one man who has given himself to the love of wisdom, and whose life bore the consequences of this pursuit of wisdom.

At one point in his defence, Socrates considers the possibility of pleading for an alternative sentence to the death penalty: perhaps banishment, or perhaps (and you see Socrates’ characteristic humor here) a life fully supported at the state’s expense. Socrates says:

I have never lived an ordinary quiet life. I did not care for the things that most people care about — making money, having a comfortable home, high military or civil rank, and all the other activities, political appointments, secret societies, party organizations, which go on in our city. . . . So instead of taking a course which would have done no good either to you or to me, I set myself to do you individually in private what I hold to be the greatest possible service. I tried to persuade each one of you not to think more of practical advantages than of his mental and moral well-being, or in general to think more of advantage than of well-being in the case of the state or of anything else. What do I deserve for behaving in this way? Some reward gentlemen, if I am bound to suggest what I really deserve, and what is more, a reward which would be appropriate for myself. Well, what is appropriate for a poor man who is a public benefactor and who requires leisure for giving you moral encouragement? Nothing could be more appropriate for such a person than free maintenance at the state’s expense.

In the end, Socrates knows that these options will not be accepted and that the government would only be happy if he were to leave the city, stop his teaching, and “mind his own business.” This, however, is not a real option. Socrates explains:

Perhaps someone may say, But surely, Socrates, after you have left us you can spend the rest of your life in quietly minding your own business.”

This is the hardest thing of all to make some of you understand. If I say that this would be disobedience to God, and that is why I cannot ‘mind my own business,’ you will not believe that I am serious. If on the other hand I tell you that to let no day pass without discussing goodness and all the other subjects about which you hear me talking and examining both myself and others is really the very best thing that a man can do, and that life without this sort of examination is not worth living, you will be even less inclined to believe me. Nevertheless that is how it is, gentlemen, as I maintain, though it is not easy to convince you of it. Besides, I am not accustomed to think of myself as deserving punishment. If I had money, I would have suggested a fine that I could afford, because that would not have done me any harm. As it is, I cannot, because I have none, unless of course you like to fix the penalty at what I could pay. I suppose I could probably afford a mina. I suggest a fine of that amount.1

“The unexamined life is not worth living.” What do you think about this? How would you like to have some pest wandering around probing you about the things you “care about,” speaking to you of “goodness” [remember Socrates’ discussion of The Good in the previous chapter?], and questioning whether your values are really worth all their effort? Would you condemn him to death or offer him government support?

Let’s, for the sake of this textbook at least, give Socrates some consideration. Perhaps there is some value to an examined life. And while we might not appreciate someone pestering us about every aspect of our dearest held values (my new car for instance), we will grant that a little examination doesn’t hurt every once in a while. And perhaps that is one function of a philosophy text, to stimulate a little needed examination. But then we are led to a further question: just what does it mean to examine one’s life? Socrates mentions such topics as “advantages,” “well-being,” “goodness,” offering “service” to others, and what kind of life is “worth living.” But it is clear that these are mentioned only as samples of the kinds of things Socrates explores in his examination of life. The “life” which is examined appears to include lots of things. And what does one do when one “examines” a life? It is clear that Socrates’ idea of life-examination is much different than our idea of a medical examination. Or is it? What is involved in this Socratic-style examination of life? Let us first take a brief look at life to learn something of the object of our examination.2

The Life we Examine

Contexts and Qualities

One way of looking at our life is to see it as “given.” Here it is. We are here in the midst of reasonings and colors and sounds and feelings and intuitions. We are born into all of these and more, apart from our own choice. Our experience of the law of gravity, our interpretation of the smile someone uses to express happiness, our sense of the difference between a question and an answer, all appear to be part of the “givens” of life.

One of the first questions about wisdom we ask is “where”? Where do we find this approach to the larger issues of life, this expertise in living, and the know-how to put them together? It is one thing to pursue the sock that seems to have walked away from its partner. You open this drawer; you search under that dresser. You look around in all the reasonable spots, and when you find it you know it. It is another thing to pursue wisdom. Where do you look for wisdom? How do you know when you have found it?

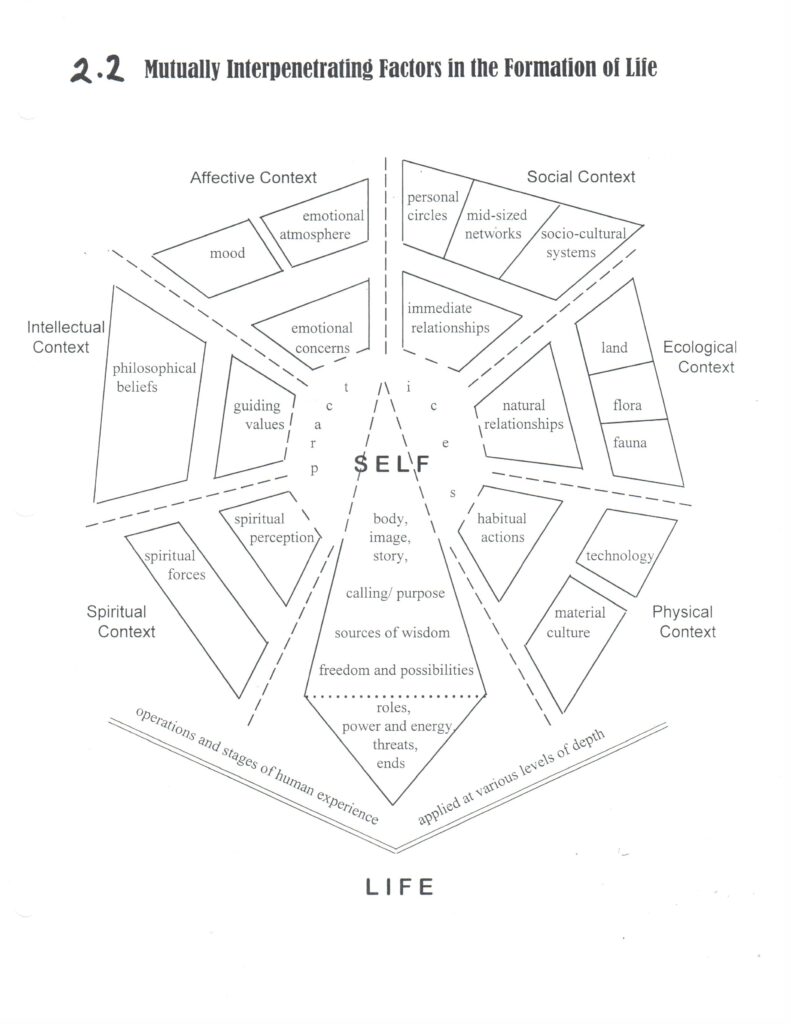

The character of the bare qualities of what is given in life are given to us in terms of contexts. Our sense of temperature is part of our physiological context, given at birth. But some are both into tropical climates and others into Artic climates, and the temperature sensitivities we inherit or develop are consequently shaped by our geographic context. We arise in social contexts: nations, ethnicities, families. We inhabit physical and ecological contexts: the land(s) in which we have lived, the technology that we use. We are the recipients of an intellectual context: the beliefs and perspectives which govern our view of things. And so on. Each of these contexts gives shape to the qualities present in the life we experience. I could go on and on here. The point is to realize that we explore the larger issues of life and we synthesize the details of life from right where we are. Wisdom is found from within the realities of our own contexts.

Some of these contexts are rather remote to us while others are quite close at hand. Think about what it means to be part of human history at the start of the twenty-first century, as opposed to all other places in human history. Now think about what it means to be a member of your family or immediate social circle. Usually our immediate context is more readily perceived. Let’s take another example. Ask yourself, “What are my guiding values in life?” Usually people are able to come up with a few guiding values. But answering the more remote questions of our philosophical beliefs regarding the nature of reality, the possibility of knowledge, the meaning of life and so on: these are a different matter. Life emerges either “out of” or “in the midst of” contexts, some of them more remote from our everyday experience and others being very present.

Relationships

These mere qualities which appear in life–colors, questions, temperature perceptions, and so on–appear with some degree of force. We are confronted with life. This patch of red, that bird call, this nagging question. This life we examine arises not as a mere sensation of arbitrary qualities. Rather life emerges as a network of relationships. Here is the land I walk on. I have a certain relationship with it. I influence it in certain ways (I can till the soil or pour used paint thinner on it) and it influences me in certain ways (providing solidity under my walk, nourishing plants, etc.). Here is my child. My child does not provide stability under my walk nor nourishes the plants from which I eat. My child and I influence each other in other sorts of ways. The patterns of mutual influence–the character of our sharing–gives specificity to our relationships with soil and child. Humans live in relationship: with ourselves, others, nature, and perhaps even more.

Sources

Some of these relationships receive special regard. We permit them more influence than others. We develop a relationship with a special friend and in so doing we give that friend room to “move” into our life. We pick up a book at a used bookstore and find ourselves reading it many times, making a conscious effort to change our practice in light of the perspective provided by this book. We settle into a particular geography–a spot by the water, a garden plot, a neighborhood–and, in time, we give ourselves to this place. We let it speak to us and to shape the character of our life. I call these special people, and places, and such, sources of wisdom. We have many kinds of sources. Particular technologies (our iPod), familiar practices (the habit of prayer), ideas (our most important values), and even feelings (we do protect our comfort, don’t we?) can be “sources” for us, forces which have a greater ability to influence our lives. Consequently, when we “examine” our life, it is especially important to take a look at those relationships that have become sources of wisdom for us. We will explore this further in the next chapter.

We learn wisdom from people around us. The Hebrew and Christian book of Proverbs states, “The way of fools seems right to them, but the wise listen to advice” (Proverbs 12:15). Who are your “advice-givers”? There are those who know us who give advice: the ones who “know the ropes” at work or the grandmother who seems to sense the way things are. And then there are those who have lived long, long ago whose wisdom we find only in the pages of books. These are the Masters of wisdom. Confucius is considered such a Master. “Tsu-chang asked about the way of the good people. The Master said, he who does not tread in the tracks [of the Ancients] cannot expect to find his way into the Inner room” (Analects, XI.19). But there are also more contemporary philosophical “advice-givers,” those who have invested time and energy exploring and communicating about knowledge, time, relationship and such. These are the authors of books of philosophy. What the contemporary philosopher may lack in depth, is sometimes compensated for by the relevance of their thoughts for the day. I suggest that you approach advice-givers with an attitude of respectful tentativeness: respectful, in that you are aware that these people have more experience or knowledge than you; tentative, in that you know that they come from their own backgrounds and with their own biases. You receive what they have to say until there is sufficient reason to doubt their wisdom.

We also learn wisdom from the world around us. We are not used to this today. We don’t know what it is like to “listen” to a piece of land for ten years to find what it might have to say. We reduce scientific wisdom to the mere accumulation of statistics, rather than seeing the statistics as one small part of a much bigger attention to the wisdom of the world. Finally, many turn to an Ultimate source of wisdom, an Other who is present in the depths of our experience and in the foundations of the world. Ourselves, others, the world around us, the Ultimate–these are our sources of wisdom. We shall explore some of the sources of wisdom and philosophy in chapter three. You will be interacting with excerpts from the works of philosophers and Masters of wisdom throughout the text.

Forces

As I mentioned above, the qualities of life–emerging from our contexts–arise with a sense of force. Many of the forces in life are not consciously noticed (for example, the force of gravity, or our habit of standing a certain distance from another when talking). Other forces are quite consciously noticed (the force of economic authority when we are fired from our job). The character of the forces within which we live defines our sense of movement of life into the present. At times–or in some situations–life is tranquil; the movement of life is a gentle flow. Other times–or in other situations–life is conflict; the movement of life is a battle as one force appears at odds with another. Some forces become stronger than others (for example, when our desire for freedom prevails over the hurdles required to overcome a disability). The development of our sources of wisdom is just such an instance. Some people have thought a great deal about their beliefs and values. Others have simply not given it much attention. While some may look to a particular book for guidance, others might look to their feelings. The state of the interplay of all these forces (physical, pyschological, social, economic, intellectual, spiritual and so on) emerges as our “life” in the immediate present.

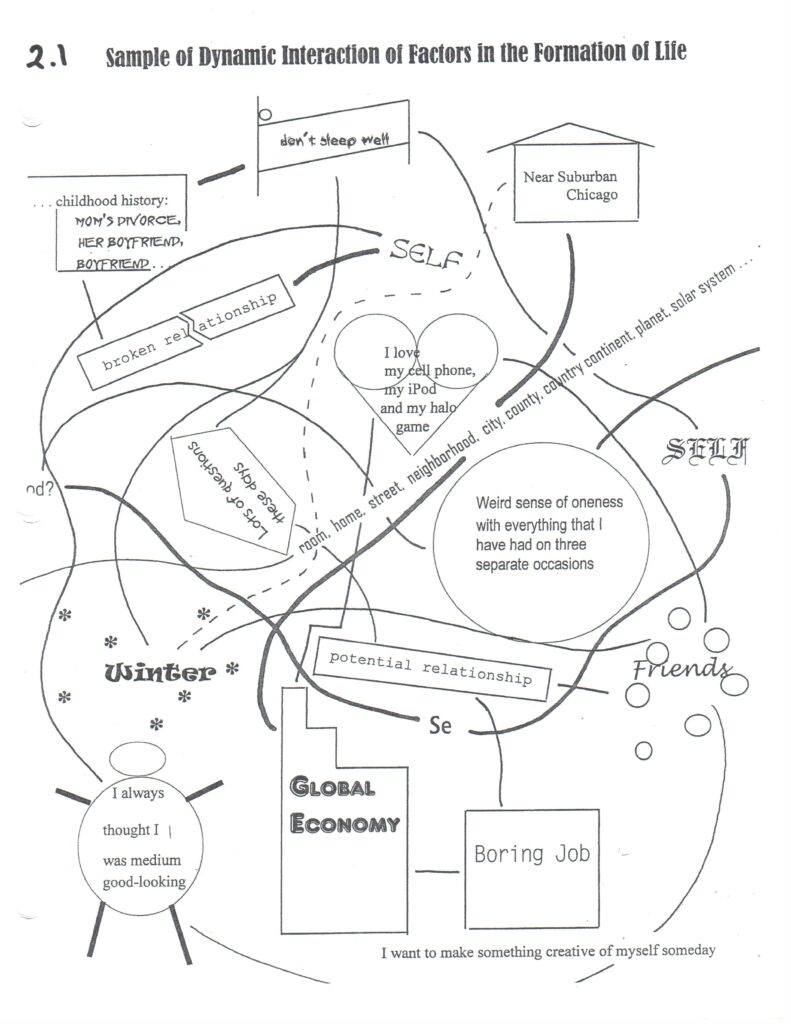

Take a look at Figure 2.1. Just spend some time with it. Follow the lines–here, and there. Which lines are strong? Which are weak? Can you imagine this person’s life? What might your own life look like? Feel free to take some time and draw your own picture.

The Currently Constructed Self

Out of all this interplay of qualities, relationships, forces and such (some stronger, some weaker), arises the self. Out of the immediate present of our conditions, we construct a self into the immediate future. Just think about it. Your classes are over for the day. What will you do now? Your choice creates a “self” into your immediate future. Or perhaps someone asks you, as you walk out of your last class, “Hey, how was your day?” Your answer to that question–the events you mention (or don’t mention), the items that are given feeling in your narrative of your day, the metaphors you use and the values they reflect–all express yourself into that encounter. No, more than that. You answer not only expresses a self, your choices of expression in this encounter also construct a self, both for yourself and for the other.

Or perhaps you wander from class into the café, and you find yourself sitting next to a stranger. And that person looks at you and says, “Tell me something about yourself.” How will you answer that request? Perhaps you will offer an image. “I’m an environmental science major.” “I’m a carpenter.” “I’m a mother.” Or you may not use these words directly, but the things you mention make it clear that “mothering” is what you’re really all about. Or perhaps you tell a story. The “story of my life.” Again, through this narrative you express and construct yourself. Or perhaps you tell the other person about your models. “I’m really a wanna-be Tiger Woods.” Or more subtly, “Didn’t you think that drive on the last hole that Tiger Woods made was just incredible. If only I could drive like that.”

By our choices, our stories, our metaphors and the like, we both express and construct our selves: a somewhat integrated, somewhat conscious, composite of our guiding values, emotional concerns, potential gains, well-established habits, central relationships, and sense of the direction of the forces in our lives. Consequently, to examine our lives is to observe this “construction site.” Ask, how has your life been “put together”? What is at the “foundation”? What is the “framework” like? What is your life “made of”? Who is building it?

Practices

Life is most concretely embodied in practices. We eat. We shop for the food we eat. We put on clothing. We care for a house or apartment. We engage in relationship with family or other forms of intimate community. We participate in our governmental process through voting or other forms of action. We go to school. We attend synagogue or some other form of religious gathering. We work at some form of employment. And so on.

Our practices, whether enacted in a single event or lived out through ongoing habits, mediate between self and immediately present relationships. And we develop practices which embody every area of life. My relationship between my self (as currently constructed) and my wife, for example, is embodied in a host of common practices (glances, speaking, touches and such). My relationship with my body is lived out through my habits of eating, exercise and so on. My relationship with ideas is lived out through my habitual contact with certain friends, with my reading patterns, my habits of thinking, and the like. Consequently, by looking carefully (by “examining”) my practices, I can learn about my self, or at least about the way I mediate myself in the context of certain relationships.

For many of us, life generally happens without us knowing it. Parents (source) remind us never to be absent from dinner together (practice) and a value for family is planted. We admire a particular sports figure (source) and we find ourselves training every day (practice) because that person trains hard. Unconsciously we adopt the value that victory comes from hard work. This value is also expressed in school work (practice in a different area). A close friend hands us a joint (practice) and we learn that the problems of this conscious world can be set aside–or intensified–while we experience another world through an altered state of consciousness (value). We discover skills. We are trained, or we fall, into a career, we enter into relationships, and life goes on, generally without much reflection on our part. Our sense of what we need in life, of “what life is about” reflects the values of those around us. We may dress different than some, or listen to our own music, but the major values of our culture are not seriously called into question. We live predominantly from the guiding values of our surroundings. There is a blend of “stumbling” into a form of life and “constructing” a life. In time the patterns and habits of our life crystalize into a particular form or model of life. One can think in terms of more general models (punk, artist, farmer . . .), or in terms of a specific “form” that is “me,” a sense of a whole somewhat-integrated individual. Again, “examining” this life involves paying attention to the character of what is formed: the connections between practices, areas of life, values, concerns, relationships, sources and more.

Triggers and Seeds

But, as we know, things happen in life. Martin gets this notion in his head to go to college and, sooner or later, he graduates. Marilyn is driving to work and a drunken driver runs a red light, hits her and cripples her. Things happen. Change. Some change grows like a seed, slowly and subtly. Something is planted that, in the right conditions, develops, matures and finally produces fruit. Other times change happens rapidly and dramatically. There is a single trigger that moved time from “then” to “now.”

We often look for triggers to explain the cause of things, the character of the way life is (“This is like it is because of x”). This way of explaining things is, however, rather shallow. As we have learned, life involves an entire interactive network of forces, sources, relationships and more. At times (as good physicians will tell you) a particular trigger is introduced (like a germ) and it has no effect because the surrounding conditions were not right. Hence the examination of life involves a look to the triggers and the seeds in the context of all that surrounds them.

Change

And so we see that this life we examine is not a static thing. As we focus our glance, it moves. It flows: sometimes peacefully, sometimes chaotically. At times, we feel we are at the mercy of forces driving us here or there. At other times we feel a freedom or power over this or that area. Sometimes we feel “in tune” with things. Other times we are “dis-integrated.” And then there is chance, spontaneity, whim. Sometimes we improvise, sometimes things just happen.

So what is this life we examine? On what are we focusing, when, like Socrates, we examine our lives and those of others? We look at the contexts and qualities, the relationships and forces, the sources and practices we embody. We explore the selves which arise, the selves we construct. We notice the triggers and seeds that push life ahead. We recognize change. This is the object of our examination, whether we are examining an individual human being or a national government. For a second, more systematic picture of this life, see Figure 2.2.

The Examination of Life

Now that we have a sense of what we are examining when we examine our lives, it is time to examine examination. If the “unexamined life is not worth living,” then it might be valueable for us to know something about just what examination is.

There are many kinds of “examination.” As a child, I used to examine my Christmas presents under the tree very carefully before the time came to open them. I would feel them, shake them, and smell them in order that I might guess what was inside. Students take “examinations,” but in these it is usually the professor that does the examining. The exam is merely a means by which the professor (who administers the examination) observes the state of a student’s learning in order to revise the next assignment or to assign grades for the class. And then there are dental or medical examinations, in which someone looks and asks questions, and pokes and prods, and takes pictures of one sort and another, all with the aim of ascertaining the condition of your health with the aim of maintaining or improving it. While these situations are varied, they all share the common character of involving a kind of (1) paying attention, (2) asking questions, and (3) drawing practical conclusions.

But what does it mean to examine a life? Some of our less than friendly friends examine our lives all the time. “Why you lazy, good-for-nothing slob. I’ve known you for ten years and you have never amounted to anything. Just when are you going to . . .” Financial advisor’s examine our lives. They take account of our contexts (our employment history), our relationships (especially our relationships with the socio-economic system), our sources of wisdom (are we conservative or speculative in our investments and why), and such in order to suggest profitable steps for our life, either short or long term. A financial advisor examines us with a particular aspect of life in mind, namely our relationship to the economic sphere of things. While our spiritual inclinations may play a small role in this examination (do we consult the stars before we invest?), this aspect of life is not generally foremost in the mind of the financial advisor.

Similarly, a counselor or psychologist examines our lives. And while this counselor might ask us about our finances (they do expect to get paid, you know!), economic factors do not generally play the major role in psychological examination. Most often we are talking about our sense of our self, our relationships, our feelings, and other sorts of things like that. But, just as a financial advisor inquires of our lives to see how it is ordered with regard to the economic sphere, so a psychologist inquires of our life to see how it is relationally and emotionally ordered. All of our life–our contexts, relationships, and sources; the forces that influence us; our beliefs and values; the self we express and construct; our habitual practices; and the dynamics of change that surround us–all of this is available for examination by the financial advisor or the counselor if it is relevant to their examination at a given point in time. But generally only certain aspects of life are highlighted by certain types of examination. So also with medical examinations.

Which brings us to philosophical examination. What did Socrates mean when he spoke of an “examined” life? If you look at our sample from Socrates’ speech, you see that he specifically mentions “persuading people” not to think more of advantage than about well-being, and “discussing goodness” and other subjects. It appears that Socrates’s kind of examining highlights the junction between beliefs, values, and the practices of everyday life. And this is philosophical examination. Socrates was a gadfly in the lives of others: probing them to consider whether they really valued what was truly valuable, poking at them to see if their lives actually were lived in harmony with their beliefs. Perhaps they had never really considered their beliefs. Shouldn’t this intellectual aspect play a part in one’s life? What happens when one just lives a life without consciously ordering it in view of one’s beliefs and values? True, finances, emotions, interpersonal relationships all might (and do) play a part in philosophical examination. But, as with any particular kind of examination some parts will necessarily receive more attention than others. And in philosophical examination, the interaction between belief/values and life takes the lead.

And what does this kind of examination involve? The same skills any examination involves. Consider the following:

- What about the skill of wonder – the ability to ask beyond the familiarity of one’s own experience and to appreciatively notice novelty? What about the role of leisure, the freedom to stop and smell the roses?

- What about the skill of paying attention – the fruit of “staying with” reality, observing it for what it is? What about the practice of meditation, bringing attention to rest on some aspect of what is?

- What about the skill of reflection – the habit of exploring one’s own (or others’) thought and life? What about the practice of self(or other)-examination, of looking deep into why we do/think/feel the way we do?

- What about the skill of inquiry – the art of asking questions? How do we learn to recognize our own doubt and to follow it? How do we learn who to question and how to question?

- What about the skill of belief – the process of taking our doubt through to a resolution in a position of reasoned faith, a faith which is neither an irrational leap nor an endless search for intellectual certainty?

- What about the skill of living – the ability to integrate beliefs, emotional concerns, and habits into a workable lifestyle which reflects both the unique person(s) involved and those values which transcend the particular?

These are the kinds of competencies necessary for learning philosophy as a love of wisdom. Think about it. Think about the wise people you have known. What are they like? Well, they don’t just blab stuff or act rashly. Wise people are people who look before they leap. They notice things. They pay attention. Lovers of wisdom are those who watch the character of life in general. They evaluate our beliefs about life based on a careful observation of life. Wise people also ask questions. Ever notice that? Your wisest friends don’t give a quick answer. They return with another question, just the right question. The wise are capable of waiting and waiting for answers. They are capable of revising and revising the questions. But then wisdom is not just about knowing. It is also about doing, living. What good does a medical examination do if we have already decided not to act on it? We have learned, with regards to medical or psychological examination, what it means to act according to the results of the exams. We know how to change our lives–to order our lives–with regard to the wisdom of the medical or psycholgical examination. We are less familiar with philosophical examination. Ask yourself: what might it mean to act according to some deeply profound insight discovered in the midst of a philosophical examination of life?

So this is the philosophical examination of life: the application of the skills of observation, inquiry, and practical application with special regards to our beliefs and values and how they connect with the other dimensions of our life. In chapters four through six we will take a closer look at these skills, particularly the skills of paying attention, asking questions, and practicing reality.

The Depth Dimension

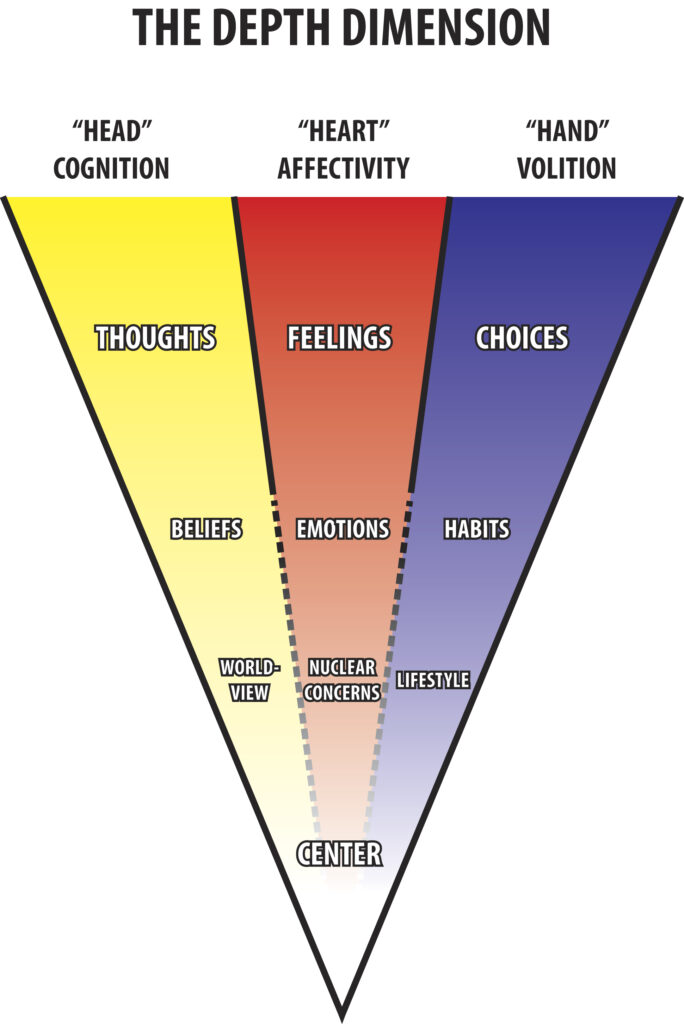

We talk about it all the time. “That movie cut me to the heart.” “These decisions are not just New Years’ resolutions, I am changing my life at the core.” “That lecture was truly deep and profound. I have to rethink everything now.” I used the term in the paragraph above, speaking about a “deeply profound” insight. Human experience arises at various levels of depth. We use “depth” language to describe levels of significance in life or to speak of degrees of impact upon the whole of human experience. Things that are deep affect us with greater significance than “ordinary,” “superficial,” or “shallow” things. We might have a particularly deep experience lasting only a few moments. Or we might go through an entire season of life where we are almost constantly challenged to the depths. But who we are at any given time is formed, in part by the levels of depth at which we are living. And when we examine our lives, we will find ourselves exploring at different levels. It is helpful to know something about these levels in order to gauge our way through the process of examination.

Level One

Let us consider head (our intellect), heart (our emotions), and hand (our “will”).3 At the most shallow level, the head is just thoughts. “Here is the pen.” “What does he mean by that statement?” “This dress is not like that dress.” And so on. “Heart,” at this level, is a matter of simple feelings. Cold, hot, grumpy, excited, afraid, worried. And so on. “Hand” (action or will) operates at this level in terms of simple choices and actions. We choose to look this way. We are actively involved in washing the dishes. We engage in conversation.

Level Two

At the next deepest level, the life of the “head” moves from thoughts to beliefs, from particular thoughts to patterns of thinking. Here, my thoughts regarding the dresses are not just simple “comparison” thoughts. Indeed, perhaps my evaluation of the dresses now introduces a serious doubt regarding my previously held belief that the best dresses were the most expensive. My question about the meaning of a friend’s statement is, at this level, not merely a question about semantics. Perhaps it is a question about my estimation of his character. “Heart” operates at Level Two as patterns of emotions. Once again, we are not dealing with simple individual feelings, but rather with established tendencies of feeling. Perhaps “grumpy” is part of a predisposition toward late afternoon irritation. On the other hand, perhaps “grumpy” is a sub-component of “depression.” Likewise perhaps “excited” is connected with a thrilling skydiving adventure, a habit enjoyed on a regular basis. Similarly, the “hand” at this level operates in terms of habit. Here we are not talking about simple choices and actions, but patterns of choices and actions. Someone interrupts me and my habit of rinsing off the dishes before washing is endangered. Habits of relating with another are established (or broken) by conversation. And so on.

The strength with which these patterns are established, the significance of the issues related to the pattern, and the length of time over which the pattern is established all factor into the perceived depth of aspects of human experience. At the upper levels of experience, we can alter thoughts, feelings, choices, without affecting the other operational systems significantly. We can choose to wash this glass before that glass without affecting us emotionally or cognitively much. But at deeper levels, change of one “part” will influence the other “parts.” Changing a well-established habit will involve emotions. Rethinking an important belief will often result in changes in how we choose to live (we will look for dresses elsewhere). And so on.

Level Three

At a still deeper level, the life of the head operates at the level of world-view. Here we are not talking simply about patterns of thinking, but of the all-encompassing framework within which the patterns of thinking “fit.” At Level Three, our question about what my friend means by a statement is not just a matter of understanding what our friend is saying, or even my beliefs regarding his character. It is rather that his comments are forcing me to rethink my whole perspective on life and reality. At this level it is a matter of how I make sense of the meaning of life in general. Thinking goes to the structures of our thought-life itself. Likewise, “heart “ operates here with regard to nuclear emotional concerns. Nuclear concerns are those concerns which drive, which structure, the overall pattern of our emotional experience in general. Our anger takes us to those hurts that have driven us to patterns of anger for much of our life. Our excitement reveals a fundamental physiological predisposition toward adrenaline rush. And so on. The “hand” at this level addresses issues of lifestyle. Perhaps hand-washing dishes (rather than loading them into a dishwasher) is part of a much larger lifestyle choice. When my spouse brings up the question of buying a dishwasher, the whole issue of lifestyle choice comes up front and center. Perhaps I have established my whole life around this particular person with whom I am now conversing. What began as a simple discussion about washing dishes is now threatening that relationship.

At level Three–the level of world-view/nuclear concern/lifestyle–it is almost impossible to effect serious change in one “part” without serious investment from the rest. Making changes in our fundamental lifestyle shapes the kinds of things which we get emotional about. Experiencing fundamental shifts in our core emotional concerns (as might happen through counseling or healing) is bound to have an effect upon the way we see the world, the way we lead our lives. Reworking our world-view cannot but have consequences upon our feelings, upon our lifestyle. This is what it means to be challenged to the depths. Everything about who we are is up for grabs. Indeed, at times, it may seem like the deeper we go, the work with this or that single area becomes less and less distinguished. To address our world-view is to address our nuclear emotional concerns. To address our life-style is to address our world-view.

And, of course, what this means is that “examining” one’s life (or the life of one’s country) can become rather threatening. While emotions do not necessarily play a part in philosophical examining, still when we threated our deeply-held values, those which have shaped our deep emotional concerns and our lifestyle itself (whether this has happened consciously or unconsciously), we can expect that there will be some rough going in the process of examination.

Level Four

Finally, some posit a level still deeper where head, heart, and hand are entirely joined at the deepest point. At this point the absolute “center” of the self is reached, and individual “parts” are transcended.

The world of philosophy deals especially with the beliefs and world-views that structure the life of our “head.” In philosophy we examine the content and the value of each of our beliefs, and we evaluate the structure of those beliefs as a world-view, the way the beliefs “fit together” as a whole. Finally, in philosophy as a love of wisdom, we consider how our beliefs, emotional concerns, and lifestyles affect one another. For especially as we deal with the deeper issues of beliefs and world-views, we cannot address “head” without touching “heart” and “hand.”

Figure 2.3 below illustrates the depth dimensions within which human experience arises. The dotted lines indicate the increasing permeability of our parts as human experience descends to deeper levels. Think about this chart for a while. How would you fill this diagram with bits and pieces of your own life? What might it look like to examine head, heart, and hand?

The Examined Life

Dis-Integration-Driven and Ongoing Examination

As I said above, we generally “stumble into” life without too much awareness of the process. We simply grow up inheriting the life that is handed us. At times we sense the tension, the dis-integration, between this and that part of life, but for the most part we live with that tension. When the tension becomes too strong, however, we are keenly aware of our own dis-integration and we are forced to “examine” our lives. We reconsider our sources of wisdom. We explore this or that practice to see what it might reveal about our guiding values. We turn to new sources of wisdom. We might even ask about those more philosophical questions which lie beneath our guiding values.

And if we wanted to (or if some philosophy teacher pushed us into it), we could examine our beliefs, our world-views, and our lifestyles without the pressure of a major dis-integration. At this point we would be intentionally examining our own lives. It is this kind of examination of life, this intentional integration of life (though, at times, a willing dis-integration), that is characteristic of the love of wisdom and therefore, of philosophy. Philosophy then, as an ongoing examination of life, then becomes the application of skills of wisdom in everyday life, intentionally applying them even when not forced into it by the circumstances of life.4

The Philosopher

The life of a philosopher is an intentionally “examined” life. Almost by definition (the love of wisdom), philosophy looks beneath the surface of things to perceive what is not always noticed, to call into question things others have not questioned and to practice what others are afraid to live. Consequently the philosopher is often found to act somewhat out of step with the culture. Pierre Hadot, a contemporary French philosopher, characterizes the view of the general culture toward the ancient philosophers and their practices as he writes,

This very rupture between the philosopher and the conduct of everyday life is strongly felt by non-philosophers. Strange indeed are those Epicureans, who lead a frugal life, practicing total equality between the men and women inside their philosophical circle; strange too, those Roman Stoics who disinterestedly administer the provinces of the empire entrusted to them and are the only ones to take seriously the laws promulgated against excess; strange as well this Roman Platonist, who on the very day he is to assume his functions, frees his slaves, and eats only every other day. . . . It is the love of this wisdom, which is foreign to the world, that makes the philosopher a stranger to it.5

The Epicurean, the Stoic, the Platonist [you have already learned about Plato; you will learn about Epicurus soon; try looking up “Stoic” in a dictionary of philosophy]: each are considered a bit “strange” to their own culture. These philosophers have examined the life they have inherited from their culture and have found some aspects wanting. And they have changed their lives accordingly. Remember, philosophy is not simply the act of reflection upon reality, but living in tune with one’s understanding of it. And if the mass of society neither reflects upon reality, nor acts in tune with it, the philosopher is bound to experience some tension with culture. We shall see this tension especially as we begin, in the final part of this book, to consider what it might mean to live out of the love of wisdom in the context of a shallow world.

Reading: An Example from Epicurus

Let us look at a specific example of an examined life, that of Epicurus, mentioned in the quote above. Epicurus (341-270 bce) was the founder of the Epicurean school of philosophy, most commonly known (and misunderstood) for its emphasis on the importance of pleasure in life. Epicurus’ views are known through letters he wrote to Herodotus and Menoeceus. Let’s start with Epicurus’ discussion about the practices of life with regard to possessions and food. Read the section of Epicusus’ recommendations to Menoeceus below and try to picture how Epicurus might have wanted Menoeceus to live, especially when it came to eating.6

————————-

We regard independence of outward things as a great good, not so as in all cases to use little, but so as to be contented with little if we have not much, being honestly persuaded that they have the sweetest enjoyment of luxury who stand least in need of it, and that whatever is natural is easily procured and only the vain and worthless hard to win. Plain fare gives as much pleasure as a costly diet, when once the pain of want has been removed, while bread and water confer the highest possible pleasure when they are brought to hungry lips. To habituate one’s self, therefore, to simple and inexpensive diet supplies all that is needful for health, and enables a man to meet the necessary requirements of life without shrinking, and it places us in a better condition when we approach at intervals a costly fare and renders us fearless of fortune.

When we say, then, that pleasure is the end and aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do by some through ignorance, prejudice, or willful misrepresentation. By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul. It is not an unbroken succession of drinking-bouts and of revelry, not sexual lust, not the enjoyment of the fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession of the soul. Of all this the beginning and the greatest good is wisdom. Therefore wisdom is a more precious thing even than philosophy; from it spring all the other virtues, for it teaches that we cannot live pleasantly without living wisely, honorably, and justly; nor live wisely, honorably, and justly without living pleasantly. For the virtues have grown into one with a pleasant life, and a pleasant life is inseparable from them.

———————

Here you catch a glimpse of the Epicurean life. It is not the life of the party animal, but neither is it the life of bitter toil. It is a life of pleasant food without overindulgence, enjoyable possessions without clutter, and the rich pursuits of wisdom. But why would anyone choose such a life? Why these pleasures rather than the immediate fulfillment of sensual delights?

———————

And since pleasure is our first and native good, for that reason we do not choose every pleasure whatsoever, but will often pass over many pleasures when a greater annoyance ensues from them. And often we consider pains superior to pleasures when submission to the pains for a long time brings us as a consequence a greater pleasure. While therefore all pleasure because it is naturally akin to us is good, not all pleasure is should be chosen, just as all pain is an evil and yet not all pain is to be shunned. It is, however, by measuring one against another, and by looking at the conveniences and inconveniences, that all these matters must be judged. Sometimes we treat the good as an evil, and the evil, on the contrary, as a good.

——————–

Epicurus says that we should not choose just any pleasure. And why? Because “pleasure is our first and native good.” His guiding value (“our good” – remember Socrates’ understanding of the good as the standard which measures other values) is pleasure: and not just the quantity of pleasure but the quality of pleasure in the context of the whole of life. For this reason we should approach life with an evaluation of the situations of life to carefully determine which actions promote the best pleasure, all things considered. At times we might choose the unpleasurable activity (housecleaning, for example), for the sake of acheiving a higher pleasure (an orderly home). Here we have come in touch with one of Epicurus’ guiding values: pleasure. Let us hear a bit more from Epicurus about this value. Notice how he treats the subject fear of death (a common fear in his day). What does this topic have to do with pleasure?

————————

Let no one be slow to seek wisdom when he is young nor weary in the search of it when he has grown old. For no age is too early or too late for the health of the soul. And to say that the season for studying philosophy has not yet come, or that it is past and gone, is like saying that the season for happiness is not yet or that it is now no more. Therefore, both old and young alike ought to seek wisdom, the former in order that, as age comes over him, he may be young in good things because of the grace of what has been, and the latter in order that, while he is young, he may at the same time be old, because he has no fear of the things which are to come. So we must exercise ourselves in the things which bring happiness, since, if that be present, we have everything, and, if that be absent, all our actions are directed towards attaining it.

. . . Accustom yourself to believing that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply the capacity for sensation, and death is the privation of all sentience; therefore a correct understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not by adding to life a limitless time, but by taking away the yearning after immortality. For life has no terrors for him who has thoroughly understood that there are no terrors for him in ceasing to live. Foolish, therefore, is the man who says that he fears death, not because it will pain when it comes, but because it pains in the prospect. Whatever causes no annoyance when it is present, causes only a groundless pain in the expectation. Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not. It is nothing, then, either to the living or to the dead, for with the living it is not and the dead exist no longer.

But in the world, at one time men shun death as the greatest of all evils, and at another time choose it as a respite from the evils in life. The wise man does not deprecate life nor does he fear the cessation of life. The thought of life is no offense to him, nor is the cessation of life regarded as an evil. And even as men choose of food not merely and simply the larger portion, but the more pleasant, so the wise seek to enjoy the time which is most pleasant and not merely that which is longest. . . .

For the end of all our actions is to be free from pain and fear, and, when once we have attained all this, the tempest of the soul is laid; seeing that the living creature has no need to go in search of something that is lacking, nor to look for anything else by which the good of the soul and of the body will be fulfilled. When we are pained because of the absence of pleasure, then, and then only, do we feel the need of pleasure. Wherefore we call pleasure the alpha and omega of a blessed life. Pleasure is our first and kindred good. It is the starting-point of every choice and of every aversion, and to it we come back, inasmuch as we make feeling the rule by which to judge of every good thing.

————————–

Epicurus repeats his point. Pleasure is our first and kindred good, the alpha and omega of a blessed life. And since we (both young and old) should seek wisdom, we ought to seek that which brings happiness. And for Epicurus happiness is of primary importance because “if that be present, we have everything.” But why choose happiness or our own pleasure at all as the good? Isn’t this a bit selfish? Has Epicurus really examined this?

Epicurus gives us a hint when he speaks of the subject of death. He suggests that we are not to fear death but simply to place our focus on the pleasure of the life before us, because, “when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.” But what does he mean by this? Once again (as with our “shopping” dialogue), we must probe Epicurus beneath his guiding values to explore the more philosophical beliefs and values that lie beneath. First, let’s look at Epicurus’ understanding of the human body and soul as he describes them to Herodotus.

—————————-

[K]eeping in view our perceptions and feelings (for so shall we have the surest grounds for belief), we must recognize generally that the soul is a corporeal thing, composed of fine particles, dispersed all over the frame, most nearly resembling wind with an admixture of heat, in some respects like wind, in others like heat. But, again, there is the third part [the soul] which exceeds . . . in the fineness of its particles and thereby keeps in closer touch with the rest of the frame. And this is shown by the mental faculties and feelings, by the ease with which the mind moves, and by thoughts, and by all those things the loss of which causes death. Further, we must keep in mind that soul has the greatest share in causing sensation. Still, it would not have had sensation, had it not been somehow confined within the rest of the frame. But the rest of the frame, though it provides this indispensable conditions for the soul, itself also has a share, derived from the soul, of the said quality; and yet does not possess all the qualities of soul. Hence on the departure of the soul it loses sentience [knowledge or awareness]. For it had not this power in itself; but something else, congenital with the body, supplied it to body: which other thing, through the potentiality actualized in it by means of motion, at once acquired for itself a quality of sentience, and, in virtue of the neighborhood and interconnection between them, imparted it (as I said) to the body also.

Hence, so long as the soul is in the body, it never loses sentience through the removal of some other part. The containing sheaths may be dislocated in whole or in part, and portions of the soul may thereby be lost; yet in spite of this the soul, if it manage to survive, will have sentience [here the body is viewed with relation to the soul as a sheath is to a knife]. But the rest of the frame, whether the whole of it survives or only a part, no longer has sensation, when once those atoms have departed, which, however few in number, are required to constitute the nature of soul. Moreover, when the whole frame is broken up, the soul is scattered and has no longer the same powers as before, nor the same notions; hence it does not possess sentience either.

For we cannot think of it as sentient, except it be in this composite whole and moving with these movements; nor can we so think of it when the sheaths which enclose and surround it are not the same as those in which the soul is now located and in which it performs these movements.

——————-

This might be a bit unfamiliar to you, so read it a few times, slowly. What do you discover? Epicurus thinks of the human being as made of body and soul, the body containing the soul like a sheath contains a knife. He understands our body or “frame” as composed of particles, just like any other physical thing. But how does he picture the soul? Epicurus considers the soul to be made of particles as well! Just as we today think of a progression from solid to fluid to gas, Epicurus takes this one step further to consider the soul as made of the finest particles of all. Consequently, when we die (and now we are getting closer to the point), the particles that make up our soul simply dissipate and we are no more.

But is that all there is to the human being? To reality? Just particles of different sizes, blowing around in space or congealing together for a time? Is there no spirit? Is there no deeper meaning to life? We must press Epicurus further still. What does he believe about ultimate reality? [are you beginning to see how these more philosophical questions are related to the ways that we live life?] Let us listen to Epicurus on reality.

———————

The whole of being consists of bodies and space. For the existence of bodies is everywhere attested by sense itself, and it is upon sensation that reason must rely when it attempts to infer the unknown from the known. And if there were no space (which we call also void and place and intangible nature), bodies would have nothing in which to be and through which to move, as they are plainly seen to move. Beyond bodies and space there is nothing which by mental apprehension or on its analogy we can conceive to exist. When we speak of bodies and space, both are regarded as wholes or separate things, not as the properties or accidents of separate things [“properties or accidents” refers to the aspects or qualities of things – like redness or size].

Again, of bodies some are composite, others the elements of which these composite bodies are made. These elements are indivisible and unchangeable, and necessarily so, if things are not all to be destroyed and pass into non-existence, but are to be strong enough to endure when the composite bodies are broken up, because they possess, a solid nature and are incapable of being anywhere or anyhow dissolved. It follows that the first beginnings must be indivisible, corporeal entities.

————————–

So there we have it. Epicurus is a committed “materialist.” He believes that there is nothing but atomic “bodies” and void to reality. Consequently, we should value the highest pleasure as the good. There is nothing to our life but a temporary configuration of variously sized particles, which shall all someday scatter. We need not fear this. It is simply the way things are. Rather we should enjoy the life we have before us right here and now, not with drinking-bouts and wantonness, but with the refined pleasures of moderate living and intellectual reflection. We have explored the philosophical beliefs that inform his guiding values and, consequently, inform the particular practices in particular areas of the ideal Epicurean life. What do you think about Epicurus’ examination of life? How do his views “fit” with his views about reality and the soul? How do you think head, heart, and hand are integrated in Epicurus’ system? Can you notice anything about his world view, his nuclear emotional concerns, his lifestyle?

Epicurus, in these letters presents the results of his own “examination” of life. He has attended to things (and especially to his senses, as he notes). He has asked about the nature of things (reality, human beings, death). He has considered the consequences of his beliefs. He has considered the guiding values of life. And he has made practical suggestions regarding how life should be lived in accordance with his beliefs and values. Here we have an Epicurean examination of life. How do you think Epicurus’ followers have lived differently than others of his day, given, for example, his views on life and death? How might you live today if you believe what Epicurus believed? What do you learn about “examination” from looking at Epicurus’ example?

Journal Assignment 2.1 Who Am I:

A Preliminary Statement of My Philosophy

Our philosophy, our love of wisdom, is expressed in life. In one sense our philosophy is simply just who we are. So as a first statement of your philosophy you will state something about who you are. I will keep confidential all information you share. I consider your journals as sacred!

First, describe briefly the context of your life. Tell me something about where you came from: family background, geography, cultural heritage, personal history. If there are key events in your life that have significantly shaped you, feel free to name them. Now when you have given the context of your life, reflect on it a bit. How has that context shaped who you are? How has it influenced your philosophy, what you think is important, true, wise, valuable and so on?

Second, imaginatively describe yourself. Think of three single words you would use to summarize yourself. Write them down. Invent a picture to describe yourself. Draw it, or tell me about that image. If you were to write a story about your life (a “once upon a time” story), what would it be titled? How would you like it to end? Now having described yourself using your imagination, reflect on what you have expressed. What do you see about your character, your way of looking at things, about your “self”? What do learn about your philosophy here?

Having given a bit of a portrait of yourself through story and image, now take some time to reflect on your guiding values and beliefs, your emotional concerns, and your well-established habits of life. Think for a moment. Who are your heroes, your mentors? If you could become anybody, who would that be? Now think about those moments when (or consider what if) you could not “get it together.” What did that look like? What does “failure” in life involve for you? Now ask yourself what a life worth living is all about? What do you really desire in life? Where do you hope to find happiness? What is the “meaning” of life? why? Finally ask what you learn from all this about your world view, your central concerns, your lifestyle. Summarize all this on a sheet of paper as a summary of your current philosophy. You will be reflecting on the development of your philosophy as the course progresses.

1. Apology, 36b-d, 37e-38b in Plato, The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, reprint, 1941, Bollingen Series (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 21–23.

2. Of course, a real “look at life” would be the fruit of a course in philosophy rather than a brief sketch at the beginning of the course. However, the section which follws is offered simply as a brief outline of the main areas to be considered in the examination of life.

3. Various typologies of the “faculties” of human experience have been proposed by philosophers East and West. The categories of mind, emotions, and will, expressed for example in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment (“Introduction,” III), have been a useful division for many and correspond neatly with the terms “head,” “heart,” and “hand.”

4. A few dangers surround one who undertakes to live the examined life. There is the danger of the over-examined life. Over-examiners are those who are constantly evaluating this and that part of life such that they never give themselves the freedom to actually live it. And then there are those who wrongly examine life: who don’t really pay attention to the right things, who ask the wrong questions, who try to put things into practice by addressing the wrong particulars. I suspect, however, in contemporary Western culture, that we suffer more from under-examination, from not considering our lives enough. We shall explore these dangers more in chapters 4-6.

5. Pierre Hadot, “Forms of Life and Forms of Discourse,” in Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), 57.

6. These excerpts are taken from T.V. Smith, ed., Philosophers Speak for Themselves: From Aristotle to Plotinus (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), 116–47.