Print or download fully-formatted pdf version here.

Chapter Outline

Introduction: Paying Attention to Our Knowing

1. What is Knowledge?

a. Terms and Concepts

b. Orientations

c. Belief and Knowledge

2. Is Knowledge Possible? True?

a. Propositional Knowledge

b. Knowledge More Broadly Considered

3. How is Knowledge Gained or Justified?

a. Reason

b. Experience

c. Intuition

4. Knowledge and the Love of Wisdom

5. The Practice of Knowing

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter we move from morality and politics to issues of knowledge (how we know things). After a brief review of the field of epistemology, you will compare “knowledge” as looked at by Confucius (Confucian) and Chuang Tzu (Taoist) as a way of getting a feel for the different “orientations” which shape our approach to knowing. You will look briefly at the relationship between “belief” and knowledge. Then you will explore the question of whether knowledge is possible at all, considering the merits of skepticism, realism, and relativism. Next, you will survey approaches to the question of the acquisition and verification of knowledge–how knowledge is gained or substantiated. Here you will compare the writings of Descartes (the rationalist) with John Locke (the empiricist) and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (the intuitivist). You will examine knowledge and the love of wisdom: a few basic principles by which your knowledge can be “wise” knowledge. And finally, you will explore how to put a consideration of knowing into practice in the real world of your every day life. Your journal exercises will give you the opportunity to get to know your own beliefs and habits with regard to knowing and to carefully examine your own process of knowing with a view to self-improvement. After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- identify some of the key questions involved in the philosophy of knowing

- give sample summaries of what knowledge is (or is about) from different perspectives and orientations

- briefly describe the positions of the primary schools of thought regarding the possibility of knowledge

- answer the question “what is truth” from a couple of perspectives

- identify the main schools of thought with regard to the gaining or verification of knowledge

- apply some basic principles by which knowledge is related to the love of wisdom

Introduction: Paying Attention to Knowing

“What do you know?” This phrase is used here and there as a greeting. Often, the response is, “Not much, how ‘bout you?” Think about it, what are we looking for when we ask this question? What is assumed in the very asking of the question? What if you took the phrase seriously? How would you answer? What do you know?

We have already touched on the subjects of knowledge and truth a number of times. “Paying attention” is itself both a preparation for knowing and a kind-of knowing in itself. “Noticing” brings something to consciousness that was not there previously (do we “know” what we notice?). Inquiry distinguishes between “what I know” and “what I don’t know.” We spoke of seeing reality through practice as a kind of “action-intuition,” in which the way things are is “known” in the midst of creative action. The nature of “knowledge” and “truth” is considered, in formal philosophical discussion, under the headings of theory of knowledge and epistemology. The questions ordinarily considered by this field usually include the following:

- What do we mean by the term “knowledge”? What does it mean to “know”?

- What is the character of knowledge? What is knowing like? Are there different “kinds” of knowledge?

- Is knowledge (in some form) possible at all?

- Is there such a thing as innate or a priori knowledge, or is all knowledge gained through experience of some sort?

- How does knowledge arise?

- How is knowledge justified? What do we mean when we say that something is “true”?

- Is it reasonable to believe that others possess “minds” as we assume ourselves to possess? On what basis? (this question is also considered under metaphysics and/or human experience)

- What is the relationship between our ethical obligations and our thoughts? Are there ethical principles which naturally flow from or lead to ways of approaching knowledge and truth? (this question is also considered under ethics)

Needless to say, as with all philosophical questions, one question leads to another.

These questions may sound esoteric but the fact of the matter is we are confronted with questions of knowledge all the time. Human beings are habitual epistemologists. Have you ever sat still for a moment and just wondered about something? That “wonder” is conducted within an implicit approach to knowing. You know something about knowing simply by the fact of your wondering. Or someone tells you some bit of information (say about a policy at work) and you respond, “How do you know that?” Now you are exploring the verification of knowledge. Some tabloid magazine claims that the threat of heart disease can be significantly be reduced by eating chocolate. Should you trust their authority? What authorities do you trust for knowledge? (and why?) You change the way you use your digital camera settings, because, as you say, “The past three times I tried it the other way it didn’t work, and so I tried it this way yesterday and it worked.” Now you are conducting and experiment, comparing experiences to verify a hypothesis. We access issues of knowledge perhaps every hour of our waking life.

Furthermore, questions of knowledge often lie nearby other important issues of philosophical belief and guiding values. You might decide that you are going to live our life for number one (your self – egoism). Why? Well, you might say. You can’t prove that there is some Almighty Force toward which I should direct my actions. You can’t prove to me that society is any more important than individual existence. What I know is that I am here and I have these desires. So I’m going to live my life for me. And your guiding values are caught up in your knowing. Questions of ethics bleed into questions of knowing (how do we know what is right?). Questions of politics also bleed into questions of epistemology (how do we know this is the right way that society should be structured?). Again and again, values and knowing are connected.

Philosophers both East and West have explored questions of this sort throughout their history. There is a vast amount of philosophical discussion about knowledge and truth. Rather than bury you in the history of epistemological thinking or dissect various epistemological arguments, we will simply “get a feel” for knowledge and truth in this chapter. We will look at a variety of writings by well-known philosophers from around the globe. We will consider a few of the basic questions listed above. And when we are through, perhaps you will know something about the wisdom of knowing and something about the relationship of knowledge to wisdom.

What is Knowledge?

Terms and Types

Let’s begin with the first basic question: just what is “knowledge” anyway? And, of course at this point, we find ourselves mired in questions not only about states of affairs, but also about language. What do we mean when we say, for example, that Chang “knows” that there is a pencil in front of him, or when we say that Tina “knows” her boyfriend, or when we say that Brigette “knows” how to use a paint sprayer? What about “knowing” a mathematical equation, or a piece of literature, or a philosophical theory? What does it mean to say that one “knows” the American Civil War, or the French Revolution? What about “knowing” God? The nuances of “knowing” shift with each use.

And the matter does not get any simpler when we explore the language (and concepts) for “knowledge” globally. For example, one of the terms for knowing in Hebrew (yada) speaks of a deep intimacy. Thus in Hebrew we can speak of a man “knowing” his wife, and her becoming pregnant. Jnana in Sanskrit refers to “cognition” generally, but can also mean “insight,” “illumination,” “wisdom,” or “enlightenment.” Just as our language might distinguish between consciousness, perception, intellection, intuition and such, so in India there is a distinction between prajna (“intuition/wisdom”), vijnana (logical knowledge), and samjna (perceptual knowledge). And the Japanese have a unique word for the knowing-ness of nature (chi-sei) incorporating nature’s ability to recognize, interpret, decide and respond flexibly to its environment. So, what do we mean when we say that we “know” (or when we say the ant colony “knows”)?

Western philosophical discussion has tended to lump the various “types” of knowledge together into three main groups: (1) knowledge by acquaintance (Tina knows her boyfriend, her suffering . . .), (2) competence knowledge or “know-how”(Brigette knows how to use a sprayer, how to do research . . .), and (3) propositional knowledge (Chang knows “that” there is a pencil, that all squares have four sides of equal length . . .). They reserve only the third category for philosophical exploration.1 While this division permits the development of a specialized inquiry, capable of precise analysis and evaluation, it leads to a neglect of other features about knowing which, when explored, end up informing our understanding of propositional knowledge itself. Systems of propositional knowledge in different cultures, while similar in many ways, develop in the context of the practical needs and world views of that society and differ accordingly (compare Indian and Western logic, for example). Some Western philosophers in the West (for example, John Dewey, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault) have begun to point out the dependencies of propositional knowledge on more practical types of knowing.

Furthermore, in many cultures, propositional knowledge is not offered as a “proof that” something is the case, but rather as a stimulus to “point” the inquirer in a direction so that he would “see” the truth with a knowledge of acquaintance (or enlightenment). The assumption is that propositional knowledge never really provides a “knowledge that.” This is reserved for the intuitive experience of truth.

Finally, our exploration of knowledge as a part of the “love of wisdom” demands a consideration of the interaction of a variety of kinds of knowledge. What kind of knowledge does it take to run a local business (or a country) wisely? What type of knowledge is used to determine that racial tensions are at the breaking point? Acquaintance? Know how? Proposition? All of the above, and it is not easy to say how one might inform the others. For these reasons, a global and practical approach to the introduction to philosophy, to the “love of wisdom,” requires us to take a broad view to the types of knowledge experienced.

Orientations

Just as our orientations affect our ways of paying attention and our approach to ethics, so our orientations affect our perspectives about knowledge. Consider, for example, what knowledge might look like for those who are more practical and social in distinction from those who are more spiritual or oriented to nature. Let’s explore this by looking at a couple of examples from the world of Chinese philosophy. Two of the primary influences in the history of Chinese philosophy have come from Confucianism and Taoism, the first more oriented to the practical and social and the latter more oriented to spirit and nature. What follows are a selection of the sayings of Confucius on knowledge and education and excerpts from the writings of Chuang Tzu, a Taoist philosopher. Read these two samples and try to get a feel for what knowledge looks like for each of these traditions.

——————————–

The Analects of Confucius2

1-1. The Master said, “Is it not pleasant to learn with a constant perseverance and application?

1-6. The Master said, A young man’s duty is to behave well to his parents at home and to his elders abroad, to be cautious in giving promises and punctual in keeping them, to have kindly feelings toward everyone, but seek the intimacy of the Good. If, when all this is done, he has any energy to spare, then let him study the polite arts [reciting the Songs, practicing archery, deportment and such].

2-11. The Master said, “If a man keeps cherishing his old knowledge, so as continually to be acquiring new, he may be a teacher of others.”

2-15. The Master said, “Learning without thought is labor lost; thought without learning is perilous.”

2-17. The Master said, “Yu, shall I teach you what knowledge is? When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it;-this is knowledge.”

2-18. The Master said, “Hear much, but maintain silence as regards doubtful points and be cautious in speaking of the rest; then you will not get into trouble. See much, but ignore what it is dangerous to have seen, and be cautious in acting upon the rest; then you will seldom want to undo your acts. He who seldom gets into trouble about what he has said and seldom does anything that he afterwards wishes he had not done, will be sure to get his reward.

6-20. The Master said, “They who know the truth are not equal to those who love it, and they who love it are not equal to those who delight in it.”

7-2. The Master said, “The silent treasuring up of knowledge; learning without satiety; and instructing others without being wearied:-which one of these things belongs to me?”

7-19,27. The Master said, I for my part am not one of those who have innate knowledge. I am simply one who loves the past and who is diligent in investigating it. . . . There may well be those who can do without knowledge; but I for my part am certainly not one of them. To hear much, pick out what is good and follow it, to see much and take due note of it, is the lower of the two kinds of knowledge [There (1) are those who do not need knowledge, (2) those who have innate knowledge, and (3) those who accumulate knowledge by hard work; Confucius places himself in the last position].

12-22. an Ch’ih asked about humanity [jen also translated “goodness”]. Confucius said, “It is to love men.” He asked about knowledge. Confucius said, “It is to know man.”

17-8. Confucius said “Yu (Tzu-lu), have you heard about the six virtues and the six obscurations?” Tzu-lu replied, “I have not.” Confucius said, “Sit down, then. I will tell you. One who loves humanity [also Goodness] but not learning will be obscured by ignorance. One who loves wisdom but not learning will be obscured by lack of principle. One who loves faithfulness but not learning will be obscured by heartlessness. One who loves uprightness but not learning will be obscured by violence. One who loves strength of character but not learning will be obscured by recklessness.”

19-6. Tzu-hsia said, “To study extensively (seriously), to be steadfast in one’s purpose, to inquire earnestly, and to reflect on what is at hand (that is, what one can put into practice)–humanity [Goodness] consists in these.”

——————————

What did you think? What does “knowledge” feel like in the world of Confucius? Now let’s try a sample from the Taoist side of things, from the writings of Chuang Tzu:

——————————

The Writings of Chuang Tzu3

How can Tao be obscured so that there should be a distinction of true and false? How can speech be so obscured that there should be a distinction of right and wrong? Where can you go and find Tao not to exist? Where can you go and find that words cannot be proved? Tao is obscured by our inadequate understanding, and words are obscured by flowery expressions. Hence the affirmations and denials of the Confucian and Motsean schools, each denying what the other affirms and affirming what the other denies. Each denying what the other affirms and affirming what the other denies brings us only into confusion.

There is nothing which is not this; there is nothing which is not that. What cannot be seen by the other person can be known by myself. Hence I say, this emanates from that; that also derives from this. This is the theory of the interdependence of this and that (or the theory of the relativity of standards or the theory of mutual production).

Nevertheless, life arises from death, and vice versa. Possibility arises from impossibility, and vice versa. Affirmation is based upon denial, and vice versa. Which being the case, the true sage rejects all distinctions and takes his refuge in Heaven (Nature). For one may base it on this, yet this is also that and that is also this. This also has its ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, and that also has its ‘right’ and ‘wrong.’ Does then the distinction between this and that really exist or not? When this (subjective) and that (objective) are both without their correlates, that is the very ‘Axis of Tao.’ And when that Axis passes through the center at which all Infinities converge, affirmations and denials alike blend into the infinite One. Hence it is said that there is nothing like using the Light. . . .

Only the truly intelligent understand this principle of the leveling of all things into One. They discard the distinctions and take refuge in the common and ordinary things. The common and ordinary things serve certain functions and therefore retain the wholeness of nature. From this wholeness, one comprehends, and from comprehension, one to the Tao. There it stops. To stop without knowing how it stops — this is Tao.

But to wear out one’s intellect in an obstinate adherence to the individuality of things, not recognizing the fact that all things are One, — that is called “Three in the Morning.” What is “Three in the Morning?” A keeper of monkeys said with regard to their rations of nuts that each monkey was to have three in the morning and four at night. At this the monkeys were very angry. Then the keeper said they might have four in the morning and three at night, with which arrangement they were all well pleased. The actual number of nuts remained the same, but there was a difference owing to (subjective evaluations of) likes and dislikes. It also derives from this (principle of subjectivity). Wherefore the true Sage brings all the contraries together and rests in the natural Balance of Heaven. This is called (the principle of following) two courses (at once).

The knowledge of the men of old had a limit. When was the limit? It extended back to a period when matter did not exist. That was the extreme point to which their knowledge reached. The second period was that of matter, but of matter unconditioned (undefined). The third epoch saw matter conditioned (defined), but judgments of true and false were still unknown. When these appeared, Tao began to decline. And with the decline of Tao, individual bias (subjectivity) arose.

Besides, did Tao really rise and decline? . . .

He who knows the activities of Nature (T’ien, literally “Heaven”) and the activities of man is perfect. He who knows the activities of Nature/Heaven lives according to Nature/Heaven. He who knows the activities of man nourishes what he does not know with what he does know, thus completing his natural span of life and will not die prematurely half of the way. This is knowledge at its supreme greatness.

However, there is some defect here. For knowledge depends on something to be correct, but what it depends on is uncertain and changeable. How do we know that what I call Nature is not really man and what I call man is not really Nature?

———————-

Can you sense the difference between Confucian knowledge viewed from an orientation toward practical social responsibility and Taoist knowledge rooted in a spiritual harmony with Nature? Perhaps the kinds of reality we commonly deal with–or the kinds of reality we find most central–influence the way we understand and experience the process of knowing reality.

So ask yourself, “What do I commonly deal with day in and day out?” “What kinds of reality are central to my world?” “What is my own “knowledge-orientation” like?” “How does my own knowledge compare with that of Confucius or Chuang Tzu?”

Belief and Knowledge

One of the ways that philosophers have defined knowledge is by linking knowledge to belief. Are all beliefs knowledge? Certainly false beliefs (like a belief that all books are made of rubber) are not knowledge. But take another example: we believe a pencil is in front of us (and indeed, it is). Is this belief “knowledge”? Well, perhaps under certain conditions. What if you ask me when my eyes are closed? Indeed, my eyes have been closed for a long time prior to your asking the question. I remembered the pencil there earlier, but since I closed my eyes someone used the pencil and put it back in front of me. Would my belief that the pencil is in front of me still be “knowledge” then? Plato gives the example of jurors in a trial who are persuaded merely by hearsay and by the cunning of the lawyer to believe that a person is guilty of robbery (yet indeed the person is guilty). Do the jurors know that the person is guilty? They have a belief and the belief is true. But this belief is not justified given the conditions of the trial.4 Thus for Plato, and for much of Western philosophy following him, knowledge required true, justified, belief.

This understanding of knowledge, in turn, has led Western philosophy into a series of questions regarding belief (just what is a belief anyway? Are there fundamental differences between ordinary beliefs about things and more “basic” beliefs upon which other beliefs depend?), truth (just how true or certain does a belief need to be in order to be “true”), and justification (how can one justify adhering to a certain belief, whether or not it may be true?). As we shall see, many of these same questions arise in the East, but in the context of other considerations.

What is knowledge? On the one hand it is obvious. One day we do not know someone and a year later that person is our best friend. We know them. We take a class at school and learn a lot of things we did not know before. On the other hand the it is difficult to say what knowledge is. It is a mystery. It encompasses various types of awareness—intimacy, know how, propositional truth–each of which shapes the others. Knowledge grows in the context of our own orientations, our contact with types of reality that are common or central to us and not to all. Our knowledge is related to our beliefs, and one way of giving confidence to our knowledge is by clarifying the character of our beliefs.

[Want to explore knowing from within? Try out JA 9.1 On Knowing Knowing]

Is Knowledge Possible? True?

Once we begin to get a sense of what knowledge might be about, the question naturally arises, “Does knowledge happen?” “Is it even possible?” This question can be asked with regards to specific bits of knowledge (I assume we can have knowledge about biology and mathematical equations, but I’m not sure we can ever know that God exists or that there are other minds, or . . . ). It can also be asked “globally” with regards to all knowledge (I don’t think we can really know anything about anything: we simply can’t be sure we are not being deceived . . .–remember Descartes’ complete doubt?).

Propositional Knowledge

For those who understand knowledge as “knowledge that”–as propositional knowledge, as true justified belief–the question of the possibility of knowledge leads to some natural divisions. Epistemological realists claim that in some form and measure knowledge about the way things are is possible. There are those who take a “strong” view of knowledge and its certainty (claiming that “knowledge” requires certainty or complete justification) and argue that, given this definition, knowledge certainly is possible, especially for some kinds of knowledge, like the knowledge of our own existence (as Descartes argues below). There are also those who take a “weak” understanding of knowledge (“knowledge” requires only a common-sense degree of probability) and argue that this kind of knowledge happens all the time. Other examples of realist approaches to knowledge could be given.

A skeptic, however (that is what we call those who question the possibility of knowledge in some form), might wonder if we are right in speaking of “knowledge,” rather than frankly admitting that we are expressing an educated guess. Perhaps knowledge is impossible in certain areas. Even though we may find ourselves “right” with regard to mathematical equations, for example, this does not mean we can provide sufficient justification to prove why we are right. British philosopher David Hume, for example, suggested that we might be overstepping our boundaries in believing in such things as “causes.” All we see is one event followed by another event. We assume from this that the one “caused” the other. But do we know this? How so? Or perhaps knowledge is impossible at all. We take a “strong” view of the nature of propositional knowledge and argue that that kind of certainty is not to be found. Or we argue that a weaker definition of knowledge is not really knowledge at all.

And then there are the relativists, those who believe that we have knowledge, but that our knowledge is neither universal nor objective. The claim of the relativist is that knowledge (or perhaps some kinds of knowledge), while giving people access to reality, is necessarily contained within words and concepts and world views that to some extent distort the reality “known.” No single person or culture has claim to “the truth.” In this sense our beliefs can be functionally adequate, yet ultimately be less than “true” or impossible to “justify.”

But then, what does it mean that something is true anyway? Some argue that truth involves some kind of correspondence between our belief or claim and the actual state of affairs. In order for my belief that a pencil is in front of me (or for there to be a god) to be “true” that belief must “correspond” in some way with reality: a pencil must actually be there (there must actually be a god). Others, arguing that complete and certain proof of this state of affairs is impossible (again, what if we are all deceived, what if our viewpoints are relative?), simply suggest that “truth” involves a statement of the way things are that is internally coherent, that makes good sense given all the features of the situation. As you can imagine, if we see knowledge in terms of true and justified belief, then one’s view of truth affects one’s view of the possibility of knowledge. Nineteenth century philosopher Friedrich Neitzsche, for example, held to a strong correspondence theory of what truth was. He also believed that truth as so defined was impossible to attain, since everyone sees reality from a limited perspective. Hence he believed that objective knowledge was not possible. It is clear that our understanding of truth is related to our understanding of knowledge.

Knowledge More Broadly Considered

These are the basic options that confront us when we approach knowledge as propositional, as true justified belief. And it is very important for us to consider what we think of knowledge from this perspective. But what happens when we consider knowledge more broadly, as an integration of a wide range of activities and states of affairs? We have suggested above that an approach to knowledge relevant to the love of wisdom involves exploration that goes beyond propositional knowledge, that it involves more than the justification of true belief. What can we conclude about the possibility of this broader range of knowledge?

While there have been realists, skeptics, and relativists throughout the history of the planet, one conclusion that arises from a broader look at knowledge is that knowledge both is and is not possible. Take another look at your readings from Confucius and Chuang Tzu above. What do you see? Confucius appears to be somewhat confident about knowledge. With diligent attention to learning (or by good birth) knowledge is possible. In time one can grow wise such that it is almost second nature to know the ways of others. On the other hand, Chuang Tzu appears less confident about knowledge. Our excerpt from Chuang Tzu ended with a question: “for knowledge depends on something to be correct, but what it depends on is uncertain and changeable. How do we know that what I call Nature is not really man and what I call man is not really Nature?” Consider the following dialogue recorded in Chuang Tzu’s writings:

——————–

Yeh Ch’u:eh asked Wang Yi, saying, “Do you know for certain that all things are the same?”

“How can I know?” answered Wang Yi. “Do you know what you do not know?”

“How can I know!” replied Yeh Ch’u:eh. “But then does nobody know?”

“How can I know?” said Wang Yi. “Nevertheless, I will try to tell you. How can it be known that what I call knowing is not really not knowing and that what I call not knowing is not really knowing? Now I would ask you this, If a man sleeps in a damp place, he gets lumbago and dies. But how about an eel? And living up in a tree is precarious and trying to the nerves. But how about monkeys? Of the man, the eel, and the monkey, whose habitat is the right one, absolutely? Human beings feed on flesh, deer on grass, centipedes on little snakes [yes, some centipedes eat snakes], owls and crows on mice. Of these four, whose is the right taste, absolutely? Monkey mates with the dog-headed female ape, the buck with the doe, eels consort with fishes, while men admire Mao Ch’iang and Li Chi, at the sight of whom fishes plunge deep down in the water, birds soar high in the air, and deer hurry away. Yet who shall say which is the correct standard of beauty? In my opinion, the doctrines of humanity and justice and the paths of right and wrong are so confused that it is impossible to know their contentions.”

“If you then,” asked Yeh Ch’u:eh, “do not know what is good and bad, is the Perfect Man equally without this knowledge?” . . .

———————-

What do you think? Is Chuang Tzu’s skepticism due to the broader range of his orientation (Nature, Spirit)? Is knowledge both possible and impossible? Are different types of knowledge more possible or less possible?

Charles S. Peirce, who wrote the article on “Fixation of Belief” you read in chapters five and six, suggests that we think of knowledge not as either objectivism, skepticism, or relativism, but rather in terms of what he calls fallibilism. What Peirce means by “fallibilism” is that humans have a tendency to fall short here or there of true knowledge for one reason or another. Part of our problem, is that we approach things, from one-side rather than from many-sides.5 Some use their heads while others know the wisdom of the heart. Some see others while others see nature. And we all see it all from our own limited abilities and perspectives. Yet we do know, however partial this knowledge is. Thus to acknowledge the “fallible” and “one-sided” character of ordinary knowledge is to acknowledge the possibility of knowledge (and especially within a simple issue like whether a pencil is in front of me now), but at the same time to recognize the complexity and work that is necessary to reach and to verify that knowledge, especially with regard to more difficult areas of life.

How Is Knowledge Gained or Justified?

Which brings us to our third basic question. How is knowledge gained or justified? Where does our knowledge come from? How do we know that what we know is really knowledge? Where do we confirm or justify the “truth”? Plato, through his analogy of the cave, encourages his readers to move beyond the prison house of the world of sight through the intellectual world into the source of reason (see chapter one, pp. ???). So long as we keep our attention to the shadows of physical life, we are stuck in illusion and have no real knowledge, no enlightenment regarding the way things really are. The light of truth is given, for Plato, to “he who would act rationally.” Epicurus, however, would disagree. Prior to his discussion of atoms and the void Epicurus gives a clear statement of how we are to come to a knowledge of the way things are. He states that, “we must by all means stick to our sensations, that is simply to the present impressions whether of the mind or of any criterion whatever, and similarly to our actual feelings, in order that we may have the means of determining that which needs confirmation and that which is obscure.” Epicurus provides us here not only with his view on the acquisition of knowledge (through sensations) but also his conviction that through sensations knowledge is not only gained, but “confirmed” or verified.

The philosophical verification of knowledge in the East has roots in the defense of the authority of the Vedic scriptures. Indian scholars recognized that certain “causes” of the arising of a cognition (for example, the hearing of the scripture) have power to bring to consciousness cognitions which could be brought to being by other operations (such as perception). So, the question was asked, “How do we apprehend the truth pertaining to a cognition which may arise from various sources and come to us through various means and media.”6 By comparing the various contributions of different “causes” of the arising of cognitions (including the hearing of the sacred scriptures), Indian philosophy began to explore the means by which cognitions are verified in a philosophical sense.

At the same time, much of Eastern philosophy simply assumes that knowledge is verified in “sight,” in enlightenment, in the intuitive perception of truth. Philosophical discussion only points the seeker to the place where discussion and “knowledge” are transcended through experience.

Experience (sensation/perception), reason, authoritative word, intuition. These vehicles have been understood as means of the arising of knowledge and as means of the verification of knowledge by philosophers everywhere. Their virtues (and weaknesses) have been debated for millennia. Let us take a closer look at three of these (reason, experience, intuition) by reading examples of each.

Reason

First, we will read a few paragraphs of Descartes’ second Meditation. If you remember, when we last left Descartes, he had endeavored to question everything until he found some certain truth that could not possibly be doubted. At the close of the first meditation he decided that he could not trust anything and was going to assume that all his thoughts were illusions caused by an evil demon. He continues the next day.

———————-

1. The Meditation of yesterday has filled my mind with so many doubts, that it is no longer in my power to forget them. Nor do I see, meanwhile, any principle on which they can be resolved; and, just as if I had fallen all of a sudden into very deep water, I am so greatly disconcerted as to be unable either to plant my feet firmly on the bottom or sustain myself by swimming on the surface. I will, nevertheless, make an effort, and try anew the same path on which I had entered yesterday, that is, proceed by casting aside all that admits of the slightest doubt, not less than if I had discovered it to be absolutely false; and I will continue always in this track until I shall find something that is certain, or at least, if I can do nothing more, until I shall know with certainty that there is nothing certain. . . .

2. I suppose, accordingly, that all the things which I see are false (fictitious); I believe that none of those objects which my fallacious memory represents ever existed; I suppose that I possess no senses; I believe that body, figure, extension, motion, and place are merely fictions of my mind. What is there, then, that can be esteemed true ? Perhaps this only, that there is absolutely nothing certain.

3. But how do I know that there is not something different altogether from the objects I have now enumerated, of which it is impossible to entertain the slightest doubt? Is there not a God, or some being, by whatever name I may designate him, who causes these thoughts to arise in my mind ? But why suppose such a being, for it may be I myself am capable of producing them? Am I, then, at least not something? But I before denied that I possessed senses or a body; I hesitate, however, for what follows from that? Am I so dependent on the body and the senses that without these I cannot exist? But I had the persuasion that there was absolutely nothing in the world, that there was no sky and no earth, neither minds nor bodies; was I not, therefore, at the same time, persuaded that I did not exist? Far from it; I assuredly existed, since I was persuaded. But there is I know not what being, who is possessed at once of the highest power and the deepest cunning, who is constantly employing all his ingenuity in deceiving me. Doubtless, then, I exist, since I am deceived; and, let him deceive me as he may, he can never bring it about that I am nothing, so long as I shall be conscious that I am something. So that it must, in conclusion, be maintained, all things being maturely and carefully considered, that this proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true each time it is expressed by me, or conceived in my mind.

———————-

Descartes has found his first indubitable principle! As he expresses it in his Discourse on Method, “I think, therefore I am” (cogito ergo sum). He may doubt everything else, but he cannot doubt that he doubts [now think about that one]. And if this is true, there must be something, some “I” that is doubting. But just what is this “I”? Descartes next considers.

———————-

4. But I do not yet know with sufficient clearness what I am, though assured that I am; and hence, in the next place, I must take care, lest perchance I inconsiderately substitute some other object in room of what is properly myself, and thus wander from truth, even in that knowledge ( cognition ) which I hold to be of all others the most certain and evident. . . .

6. But as to myself, what can I now say that I am, since I suppose there exists an extremely powerful, and, if I may so speak, malignant being, whose whole endeavors are directed toward deceiving me ? Can I affirm that I possess any one of all those attributes of which I have lately spoken as belonging to the nature of body ? After attentively considering them in my own mind, I find none of them that can properly be said to belong to myself. To recount them were idle and tedious. Let us pass, then, to the attributes of the soul. The first mentioned were the powers of nutrition and walking; but, if it be true that I have no body, it is true likewise that I am capable neither of walking nor of being nourished. Perception is another attribute of the soul; but perception too is impossible without the body; besides, I have frequently, during sleep, believed that I perceived objects which I afterward observed I did not in reality perceive. Thinking is another attribute of the soul; and here I discover what properly belongs to myself. This alone is inseparable from me. I am–I exist: this is certain; but how often? As often as I think; for perhaps it would even happen, if I should wholly cease to think, that I should at the same time altogether cease to be. I now admit nothing that is not necessarily true. I am therefore, precisely speaking, only a thinking thing, that is, a mind, understanding, or reason, terms whose signification was before unknown to me. I am, however, a real thing, and really existent; but what thing? The answer was, a thinking thing. . . .

———————

Descartes now moves from the indubitable starting point to further points. Given that “I think, therefore I am,” what can be known about this “I” that is? Notice how he walks step by step to his conclusion. Once again, he accepts no conclusion that can be doubted (for example, by affirming the various attributes about his body). He explores himself attribute by attribute, rejecting each, until he hits “thinking.” He reasons that, based on his earlier indubitable starting point, thinking and this “I” are inseparable. Therefore, Descartes concludes, this self that he knows to exists is essentially a thinking thing. He has now come to some sense of the nature of the “in here.” But what about the “out there”? How can we know the nature of what is out there based on this understanding of a thinking being? He explores this question by using an example. What can he know (and how does he know) the nature of wax?

——————–

11. Let us now accordingly consider the objects that are commonly thought to be [the most easily, and likewise] the most distinctly known, viz., the bodies we touch and see; not, indeed, bodies in general, for these general notions are usually somewhat more confused, but one body in particular. Take, for example, this piece of wax; it is quite fresh, having been but recently taken from the beehive; it has not yet lost the sweetness of the honey it contained; it still retains somewhat of the odor of the flowers from which it was gathered; its color, figure, size, are apparent ( to the sight); it is hard, cold, easily handled; and sounds when struck upon with the finger. In fine, all that contributes to make a body as distinctly known as possible, is found in the one before us. But, while I am speaking, let it be placed near the fire–what remained of the taste exhales, the smell evaporates, the color changes, its figure is destroyed, its size increases, it becomes liquid, it grows hot, it can hardly be handled, and, although struck upon, it emits no sound. Does the same wax still remain after this change? It must be admitted that it does remain; no one doubts it, or judges otherwise. What, then, was it I knew with so much distinctness in the piece of wax? Assuredly, it could be nothing of all that I observed by means of the senses, since all the things that fell under taste, smell, sight, touch, and hearing are changed, and yet the same wax remains.

12. It was perhaps what I now think, viz., that this wax was neither the sweetness of honey, the pleasant odor of flowers, the whiteness, the figure, nor the sound, but only a body that a little before appeared to me conspicuous under these forms, and which is now perceived under others. But, to speak precisely, what is it that I imagine when I think of it in this way? Let it be attentively considered, and, retrenching all that does not belong to the wax, let us see what remains. There certainly remains nothing, except something extended, flexible, and movable. But what is meant by flexible and movable ? Is it not that I imagine that the piece of wax, being round, is capable of becoming square, or of passing from a square into a triangular figure ? Assuredly such is not the case, because I conceive that it admits of an infinity of similar changes; and I am, moreover, unable to compass this infinity by imagination, and consequently this conception which I have of the wax is not the product of the faculty of imagination. But what now is this extension ? Is it not also unknown ? for it becomes greater when the wax is melted, greater when it is boiled, and greater still when the heat increases; and I should not conceive [clearly and] according to truth, the wax as it is, if I did not suppose that the piece we are considering admitted even of a wider variety of extension than I ever imagined, I must, therefore, admit that I cannot even comprehend by imagination what the piece of wax is, and that it is the mind alone which perceives it. I speak of one piece in particular; for as to wax in general, this is still more evident. But what is the piece of wax that can be perceived only by the [understanding or] mind? It is certainly the same which I see, touch, imagine; and, in fine, it is the same which, from the beginning, I believed it to be. But (and this it is of moment to observe) the perception of it is neither an act of sight, of touch, nor of imagination, and never was either of these, though it might formerly seem so, but is simply an intuition (inspectio) of the mind, which may be imperfect and confused, as it formerly was, or very clear and distinct, as it is at present, according as the attention is more or less directed to the elements which it contains, and of which it is composed. . . .

———————–

Descartes seems to learn something about this wax. But his point in this reflection is actually less about the nature of the existence and character of the “out there” (he covers this in his fifth meditation), than about the way he knew something about the out there. As he mentioned in the first meditation, so he suggests here. Senses can be deceiving. Even our imagination is not capable of grasping the “reality” of the wax. It is actually the mind which perceives, which knows, the wax. And this is Descartes’ conclusion at the end of the second meditation: knowledge is gained (and verified) not through the senses, but through reason.

————————

16. But, in conclusion, I find I have insensibly reverted to the point I desired; for, since it is now manifest to me that bodies themselves are not properly perceived by the senses nor by the faculty of imagination, but by the intellect alone; and since they are not perceived because they are seen and touched, but only because they are understood [or rightly comprehended by thought ], I readily discover that there is nothing more easily or clearly apprehended than my own mind. But because it is difficult to rid one’s self so promptly of an opinion to which one has been long accustomed, it will be desirable to tarry for some time at this stage, that, by long continued meditation, I may more deeply impress upon my memory this new knowledge.

————————

Reality is perceived by the intellect alone. Descartes is the model rationalist, one who believes that knowledge is gained or verified through reason. Plato and Leibniz in the West, and perhaps the Nyaya school in India, could also be seen as rationalists.

Experience

Now let’s consider another approach to the acquisition and verification of knowledge. John Locke, a British philosopher, published his Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1690, fifty years after Descartes published his Meditations. In this book he explores the nature of “knowing” in great detail. At the beginning of the book, Locke carefully argued that there are no innate (or “native”) principles in the human mind. Having dismissed this notion, Locke, in the excerpt below, explores the ultimate sources of our “ideas”: whatever it is that we think, feel, or desire.

——————–

1. Idea is the object of thinking. Every man being conscious to himself that he thinks; and that which his mind is applied about whilst thinking being the ideas that are there, it is past doubt that men have in their minds several ideas,- such as are those expressed by the words whiteness, hardness, sweetness, thinking, motion, man, elephant, army, drunkenness, and others: it is in the first place then to be inquired, How he comes by them?

I know it is a received doctrine, that men have native ideas, and original characters, stamped upon their minds in their very first being. This opinion I have at large examined already; and, I suppose what I have said in the foregoing Book will be much more easily admitted, when I have shown whence the understanding may get all the ideas it has; and by what ways and degrees they may come into the mind;- for which I shall appeal to every one’s own observation and experience.

2. All ideas come from sensation or reflection. Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas:- How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE. In that all our knowledge is founded; and from that it ultimately derives itself. Our observation employed either, about external sensible objects, or about the internal operations of our minds perceived and reflected on by ourselves, is that which supplies our understandings with all the materials of thinking. These two are the fountains of knowledge, from whence all the ideas we have, or can naturally have, do spring.

3. The objects of sensation one source of ideas. First, our Senses, conversant about particular sensible objects, do convey into the mind several distinct perceptions of things, according to those various ways wherein those objects do affect them. And thus we come by those ideas we have of yellow, white, heat, cold, soft, hard, bitter, sweet, and all those which we call sensible qualities; which when I say the senses convey into the mind, I mean, they from external objects convey into the mind what produces there those perceptions. This great source of most of the ideas we have, depending wholly upon our senses, and derived by them to the understanding, I call SENSATION.

4. The operations of our minds, the other source of them. Secondly, the other fountain from which experience furnisheth the understanding with ideas is,- the perception of the operations of our own mind within us, as it is employed about the ideas it has got;- which operations, when the soul comes to reflect on and consider, do furnish the understanding with another set of ideas, which could not be had from things without. And such are perception, thinking, doubting, believing, reasoning, knowing, willing, and all the different actings of our own minds;- which we being conscious of, and observing in ourselves, do from these receive into our understandings as distinct ideas as we do from bodies affecting our senses. This source of ideas every man has wholly in himself; and though it be not sense, as having nothing to do with external objects, yet it is very like it, and might properly enough be called internal sense. But as I call the other SENSATION, so I Call this REFLECTION, the ideas it affords being such only as the mind gets by reflecting on its own operations within itself. By reflection then, in the following part of this discourse, I would be understood to mean, that notice which the mind takes of its own operations, and the manner of them, by reason whereof there come to be ideas of these operations in the understanding. These two, I say, viz. external material things, as the objects of SENSATION, and the operations of our own minds within, as the objects of REFLECTION, are to me the only originals from whence all our ideas take their beginnings. The term operations here I use in a large sense, as comprehending not barely the actions of the mind about its ideas, but some sort of passions arising sometimes from them, such as is the satisfaction or uneasiness arising from any thought.

5. All our ideas are of the one or the other of these. The understanding seems to me not to have the least glimmering of any ideas which it doth not receive from one of these two. External objects furnish the mind with the ideas of sensible qualities, which are all those different perceptions they produce in us; and the mind furnishes the understanding with ideas of its own operations.

These, when we have taken a full survey of them, and their several modes, combinations, and relations, we shall find to contain all our whole stock of ideas; and that we have nothing in our minds which did not come in one of these two ways. Let any one examine his own thoughts, and thoroughly search into his understanding; and then let him tell me, whether all the original ideas he has there, are any other than of the objects of his senses, or of the operations of his mind, considered as objects of his reflection. And how great a mass of knowledge soever he imagines to be lodged there, he will, upon taking a strict view, see that he has not any idea in his mind but what one of these two have imprinted;- though perhaps, with infinite variety compounded and enlarged by the understanding, as we shall see hereafter.

————————

Whereas Descartes might say that his ideas about wax came ultimately from reason, from the intellect, and whereas Descartes might be cautious about the reliability of the senses for verifying knowledge, Locke states clearly that ideas come from one place and one only: experience. Knowledge comes either from “sensation” which brings data to the mind from the outside, or from “reflection” which considers this data from within. Hear Locke’s debate against those who might argue that the soul always thinks, even children, even in sleeping (a debate with those who think that knowledge comes from the reason and not from experience):

————————

17. If I think when I know it not, nobody else can know it. Those who so confidently tell us that the soul always actually thinks, I would they would also tell us, what those ideas are that are in the soul of a child, before or just at the union with the body, before it hath received any by sensation. The dreams of sleeping men are, as I take it, all made up of the waking man’s ideas; though for the most part oddly put together. It is strange, if the soul has ideas of its own that it derived not from sensation or reflection, (as it must have, if it thought before it received any impressions from the body,) that it should never, in its private thinking, (so private, that the man himself perceives it not,) retain any of them the very moment it wakes out of them, and then make the man glad with new discoveries. Who can find it reason that the soul should, in its retirement during sleep, have so many hours’ thoughts, and yet never light on any of those ideas it borrowed not from sensation or reflection; or at least preserve the memory of none but such, which, being occasioned from the body, must needs be less natural to a spirit? It is strange the soul should never once in a man’s whole life recall over any of its pure native thoughts, and those ideas it had before it borrowed anything from the body; never bring into the waking man’s view any other ideas but what have a tang of the cask, and manifestly derive their original from that union. If it always thinks, and so had ideas before it was united, or before it received any from the body, it is not to be supposed but that during sleep it recollects its native ideas; and during that retirement from communicating with the body, whilst it thinks by itself, the ideas it is busied about should be, sometimes at least, those more natural and congenial ones which it had in itself, underived from the body, or its own operations about them: which, since the waking man never remembers, we must from this hypothesis conclude either that the soul remembers something that the man does not; or else that memory belongs only to such ideas as are derived from the body, or the mind’s operations about them. . . .

20. No ideas but from sensation and reflection, evident, if we observe children. I see no reason, therefore, to believe that the soul thinks before the senses have furnished it with ideas to think on; and as those are increased and retained, so it comes, by exercise, to improve its faculty of thinking in the several parts of it; as well as, afterwards, by compounding those ideas, and reflecting on its own operations, it increases its stock, as well as facility in remembering, imagining, reasoning, and other modes of thinking. . . .

22. The mind thinks in proportion to the matter it gets from experience to think about. Follow a child from its birth, and observe the alterations that time makes, and you shall find, as the mind by the senses comes more and more to be furnished with ideas, it comes to be more and more awake; thinks more, the more it has matter to think on. After some time it begins to know the objects which, being most familiar with it, have made lasting impressions. Thus it comes by degrees to know the persons it daily converses with, and distinguishes them from strangers; which are instances and effects of its coming to retain and distinguish the ideas the senses convey to it. And so we may observe how the mind, by degrees, improves in these; and advances to the exercise of those other faculties of enlarging, compounding, and abstracting its ideas, and of reasoning about them, and reflecting upon all these; of which I shall have occasion to speak more hereafter.

——————-

Sleepers, children, all of us–according to Locke–find the origins of their ideas not in reason, but rather in experience. And ultimately he places the strongest emphasis on sensation.

——————-

23. A man begins to have ideas when he first has sensation. What sensation is. If it shall be demanded then, when a man begins to have any ideas, I think the true answer is,- when he first has any sensation. For, since there appear not to be any ideas in the mind before the senses have conveyed any in, I conceive that ideas in the understanding are coeval with sensation; which is such an impression or motion made in some part of the body, as produces some perception in the understanding. It is about these impressions made on our senses by outward objects that the mind seems first to employ itself, in such operations as we call perception, remembering, consideration, reasoning, &c.

——————-

John Locke is a good example of an empiricist, who believes that knowledge is gained or verified through experience. Debates between rationalists and empiricists have raged throughout the history of Western philosophy. What do you think? Are you more of an empiricist or a rationalist? Why?

A unique synthesis of empiricist and rationalist concerns was developed by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781). Kant, following Locke and the empiricists, agreed that experience was necessary for knowledge. But experience was not enough to give us knowledge of such things as “being,” the soul, cause and effect, time, space, and other such matters–matters which are necessary for human existence as we know it. Kant concluded that reason contributes its own part to the knowing process. But–and here’s the trick–what reason provides is the structure of looking at (or interpreting) this data, a structure not verifiable in the data itself. Thus what we call “knowledge” is really just the way the mind constructs an interpretation of the data it receives. Is the mind “right” about this construction of reality? There is no way of really knowing with any kind of certainty. All we have is the possibility of reasoning what must be the necessary conditions for our thinking or acting or appreciating in the way we do. Constructivism is one term used by philosophers to identify approaches to knowledge similar to Kant. You can see the possibilities of the constructivist position. On the one hand it reconciles the conflicts between rationalism and empiricism. It is clear that in terms of the sources of knowledge, of how knowledge is gained, both experience and understanding play their own part. But on the other hand, just what is this “knowledge” we have which the mind constructs? And when it comes to the question of verification, how do we verify the “truth” of a given belief?

Intuition

Let us look at one more sample of an approach to the sources and verification of knowledge. This time, let us look to a more contemporary Indian philosopher. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888-1975) was first a philosopher in India, and later in England, one of the first to integrate Western and Indian philosophical ideas. He then returned to India and ultimately, after India’s independence, became president of the country from 1962-1967. Indians celebrate “Teacher’s Day” on September 5th in his honor. Radhakrishnan emphasizes the place of “intuition” in his works. Let us hear how Radhakrishnan discusses this concept in a few excerpts from lectures he delivered in England around 1930.7

————————

There is a knowledge which is different from the conceptual, a knowledge by which we see things as they are, as unique individuals and not as members of a class or units in a crowd. It is non-sensuous, immediate knowledge. Sense knowledge is not the only kind of immediate knowledge. As distinct from sense knowledge or pratyaksa (literally presented to a sense), the Hindu thinkers use the term aparoksa for the non-sensuous immediate knowledge. This intuitive knowledge arises from an intimate fusion of mind with reality. It is knowledge by being and not by senses or by symbols. It is awareness of the truth of things by identity. We become one with the truth, one with the object of knowledge. The object known is seen not as an object outside the self, but as a part of the self. What intuition reveals is not so much a doctrine as a consciousness; it is a state of mind and not a definition of the object. Logic and language are a lower form, a diminution of this kind of knowledge. thought is a means of partially manifesting and presenting what is concealed in this greater self-existent knowledge. Knowledge is an intense and close communion between the knower and the known. In logical knowledge there is always the duality, the distinction between the knowledge of a thing and its being. Thought is able to reveal reality, because they are one in essence; but they are different in existence at the empirical level. Knowing a thing and being it are different. So thought needs verification.

There are aspects of reality where only this kind of knowledge is sufficient. Take, e.g., the emotion of anger. Sense knowledge of it is not possible in regard to its superficial manifestations. Intellectual knowledge is not possible until the data are supplied from somewhere else, and sense cannot supply them. Before the intellect can analyze the mood of anger, it must get at it and it cannot get at it by itself. We know what it is to be angry by being angry. No one can understand fully the force of human love or parental affection who has not himself been through them. Ingrained emotions are quite different from felt ones.

The great illustration of intuitive knowledge given by Hindu thinkers is the knowledge of self. We become aware of our own self, as we become aware of love or anger, directly by a sort of identity with it. Self-knowledge is inseparable from self-existence. It seems to be the only true and direct knowledge we have: all else is inferential. Samkara [Shankara] says that self-knowledge which is neither logical nor sensuous is the presupposition of every other kind of knowledge. It alone is beyond doubt for ‘it is of the essential nature of him who denies it.’ It is the object of the notion of self and it is known to exist on account of its immediate presentation. It cannot be proved, since it is the basis of all proof. . . .

———————-

How does Radhakrishnan understand intuition? He makes a comparison between sense and reason, which operate on a division between the knower and the known, and intuition, which arises out of a profound “communion” between the knower and the known. He gives the examples of our own awareness of our own anger and our own self. How can we “get at it,” how can we “know” our anger apart from an intuitive union within ourselves? He quotes from Shankara (remember him in chapter 3?), but in his discussion of the indubitable character of this knowledge, does he not also sound a bit like Descartes? Go back to your reading of Shankara. Explore his discussion of the self (“no difference between cause and effect” – “That Thou Art”). Why do you think Radhakrishnan refers to Shankara in his discussion of intuition and self-knowledge here? Notice how Radhakrishnan singles out “sense knowledge” and “intellectual knowledge” for attack. He argues in the following excerpt that neither empiricism nor rationalism–the primary schools of epistemology in the West–are satisfactory ways of describing the grounding of knowledge. Here he refers specifically to Descartes and Locke.

———————-

Many Western thinkers confirm this view of Samkara. The scepticism of Descartes reaches its limits and breaks against the intuitive certainty of self consciousness: Cogito ergo sum [I think, therefore I am]. Unfortunately, Descartes’ expression is misleading. Self-knowledge is far too primitive and simple to admit of an ergo [I am]. If the ‘I am’ depends on an ‘I think,’ the ‘I think’ must also depend on another ‘ergo,’ and so on, and it will land us in infinite regress. . . It is not an inference, but the expression of a unique fact. In self-consciousness, thought and existence are indissolubly united. The self is the first absolute certainty, the foundation of all logical proofs. . . Even Locke, who waged a vigorous polemic against innate ideas, concedes the reality of intuitions. ‘As for our own existence,’ says he, ‘we perceive it so plainly and so certainly that it neither needs nor is capable of proof.’ . . .

———————

While having value in their own place, Radhakrishnan finds empiricism and rationalism are insufficient to provide a grounding for knowledge in its deepest forms, a point affirmed, he argues, by the founders of each of these schools of thought. Our deepest convictions about the real, the right, the beautiful, our most important assumptions are grounded not in perception or in inference (reason), but in intuition. In the West, some philosophers talk about “basic beliefs,” beliefs which are grounded neither in experience or reason but which count as knowledge independent of either and which serve as the foundations for both. Perhaps Radhakrishnan is arguing that a unique foundation for basic beliefs is to be identified in intuition.

———————–

The deepest things of life are known only through intuitive apprehension. We recognize their truth but do not reason about them. In the sphere of values we depend a good deal on this kind of knowledge. Both the recognition and creation of values are due to intuitive thinking. Judgments of fact require dispassionateness; judgments of value depend on vital experience. Whether a plan of action is right or wrong, whether an object presented is beautiful or ugly can be decided only by men whose conscience is educated and whose sensibility is trained. Judgments of fact can be easily verified while value-judgments cannot. Sensitiveness to quality is a function of life, and is not achieved by mere learning. It is dependent upon the degree of development of the self. . . .

The deepest convictions by which we live and think, the root principles of all thought and life, are not derived from perceptual experience or logical knowledge. How do we know that the universe is in its last essence sound and consistent? Hindu thinkers affirm that the sovereign concepts which control the enterprise of life are profound truths of intuition born of the deepest experiences of the soul. For our senses and intellect the world is a multiplicity of more or less connected items external to themselves, and yet logic believes that this confused multiplicity is not final, and the world is an ordered whole. The synthetic activity of knowledge becomes impossible an unmeaning if we do not assume the rationality of the world. It is not arrived at by way of speculative construction; we have not searched the outermost bounds of nature or the innermost recesses of the soul to be able to say that the systematic unity of the world is a logical conclusion. While thought cannot stir without faith in the consistency of the world, for thought itself it is only a postulate, a matter of faith. Out logical impulse is a power of the self, and therefore possesses in its own being the vision of the law that governs the universe. The order of nature is a dependable unity because the self is itself a unity. So long as I remain myself, everything is capable of being thought as a unity. Thought is guided by the spirit in man, the divine in us. The orderedness of the universe is a conviction of life which is beyond mere logic. It will not do to be merely logical. It is necessary to be reasonable. We have to start with right premises if logic is to yield fruitful results. Intuition is as strong as life itself from whose soul it springs. It tells us that the world is part of a spiritual order, though we may not have clear and consistently logical evidence for it. Through intuition we become aware of the harmony which critical intelligence attempts to achieve. In spite of so much obvious arbitrariness we assume the trustworthiness of nature. Scientific experience increasingly confirms the venture of faith, but at no stage does the act of faith become a logically demonstrated proposition. Our whole logical life grows on the foundations of a deeper insight, which proves to be wisdom and not error, because it is workable. . . .

If intuitive knowledge does not supply us with universal major premises, which can neither question nor establish, our life will come to an end. The ethical soundness, the logical consistency and the aesthetic beauty of the universe are assumptions for science and logic, art, and morality, but are not irrational assumptions. They are the apprehensions of the soul, intuitions of the self quite as rational as faith in the physical world or the intellectual schemes, though not grasped in the same way. . . .

———————-

Did you notice what Radhakrishnan is doing here? He is arguing that at the roots of discussion of reality, morality, and beauty (metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics) is an intuitive knowledge that transcends both the framework and capabilities of sensation and reason. Radhakrishnan, the quintessential intuitionist (believing that knowledge is gained or verified through a non-sensual unitive grasp of reality) concludes his discussion of the need for intuition in philosophy with the following words:

———————-

Unless the mind is set free and casts away all desire and anxiety, all interest and regret, it cannot enter the world of pure being and reveal it. It is prior to the distinction of subject and object, of truth and error, which arise at the reflective level. No logical knowledge is possible of that which underlies all logical knowledge. The living self is the final ground of all thought, and as independent of any further ground is free and absolute. Similarly ethical certainty requires a highest from which all other ends are derived, an end which flows from the very self and gives meaning and significance to the less general ethical ends. The ultimate assumption of all is the spirit in us, the divine in man. Life is God, and the proof of it is life itself.

———————-

Located in some kind of juncture between empiricism and intuitionism is the acceptance of “extra-sensory” perception. What of those who claim to perceive the thoughts of others, or to see or hear things at a great distance from their occurance? What about those who claim to have known the distant past or future? Do we acknowledge their claims as “knowledge”? Would we receive extra-sensory data as justification for philosophical claims about reality? While most contemporary philosophers in the West would be cautious (at the least) to welcome “knowledge” from such sources, the history of philosophy in India, for example, assumes the value of information gain through extra-sensory sources.8

Sense experience, reason, construction, intuition. How are we to justify knowledge? Epistemology as an exploration of true justified belief has, in recent centuries in the West, rowed itself into some treacherous waters (some have even declared the end of epistemology). Some Existentialists have hopped aboard subjectivity. Others have suggested various pragmatic ways of justifying knowledge. Others despair of any real, universal, or truly justified “knowledge” in view of a constructivism or relativism related to a host of factors that shape the nature of our knowing and the nature of the known (social, economic, gender, historical . . .). And still others turn to interpretation (often referred to as “hermeneutics”) for a path into knowing.

Knowledge and the Love of Wisdom

But what if we look at knowledge not simply as “true justified belief,” but in a broader perspective? What if we look at knowledge from the perspective of a global, practical approach to the love of wisdom? Where does this way of looking at knowledge take us? I would suggest a few basic principles.9

Knowledge is broader than propositional statements

First, by definition we have already established that we are not looking at knowledge merely in terms of propositional statements. Rather we are including a wide range of possibilities in our understanding of knowledge. And indeed, this seems to be an interest of other philosophers as well. The Taoists “knowledge” is different from the Confucian “knowledge.” Clearly Radhakrishnan’s discussion of intuition as an intimate unitive knowledge includes some kind of knowledge of acquaintance. Versions of pragmatism and existentialism place propositional knowing secondary to one or another form of know-how, or living knowledge. And we could go on. The main point is that we understand knowledge as including a wide range of phenomena.

Knowing employs different habits of mind in order to learn something new

Second, if we are to understand knowledge broadly, we must recognize that a number of mental operations are involved in knowledge. We think. We feel. We act. We exercise awareness. We pay attention. We experience. We perceive. We ask questions. We evaluate. We decide what to believe. We integrate. We practice reality. This is not a simple constructivism whereby “the mind” provides a few fundamental categories within which the data from the senses are interpreted. Rather knowing is a complex process involving a number of distinct procedures. And in doing so we apprehend something that was not present to our mind before.

Given this wide range of distinct operations involved in knowing, we can expect that there is no single means of knowledge acquisition or justification. Different elements and stages of this knowledge process will require different types of justification. Different kinds of reality and different aspects of reality are apprehended by means of different kinds of knowing. It is not that knowledge is impossible; rather it simply requires a complex system of verification. At one point we will be turning to the senses checking to see if our assumptions really bear out in repeated observation. At other times we will use reason to clarify fallacies of thinking. At times our feelings know things regarding which reason is blind. Some forms of justification will require a certain attention of “correspondence.” Other forms will require an attention to the inner “coherence” of our beliefs. There are ways of checking the authenticity of a single operation (we clarify our feelings by reflectively “dwelling with them” for a while) and there are ways in which one operation acts as a check on another (we use experimentation to evaluate a creative hypothesis). If ideas have some kind of “reality,”and if it is wise to consider reality in terms a multiplicity of “causes” (for this see the chapter on reality) it will be wise, therefore, to consider the multiplicity of causes of particular ideas and “cognitions” as a way of exploring the source and/or verification of knowledge.

The art of reasoning is a fallible process

Third, given this range of operations involved in the knowing process, we can expect that no single human will be able to perform all of them to perfection. Hence, we must affirm Charles Peirce’s principle of “fallibility.”10 Some are thinkers, others are feelers, others intuitively integrate things in a whole. We fix beliefs through tenacity. We fall prey to the Idols of the Tribe or the Marketplace. We miss-understand by trying put too much together in a box, erasing the profound “otherness” that knowing should provide. We miss-understand by failing to recognize patterns that hold things together. While we all know, we do so in part.

Knowing has a real shape in our lives

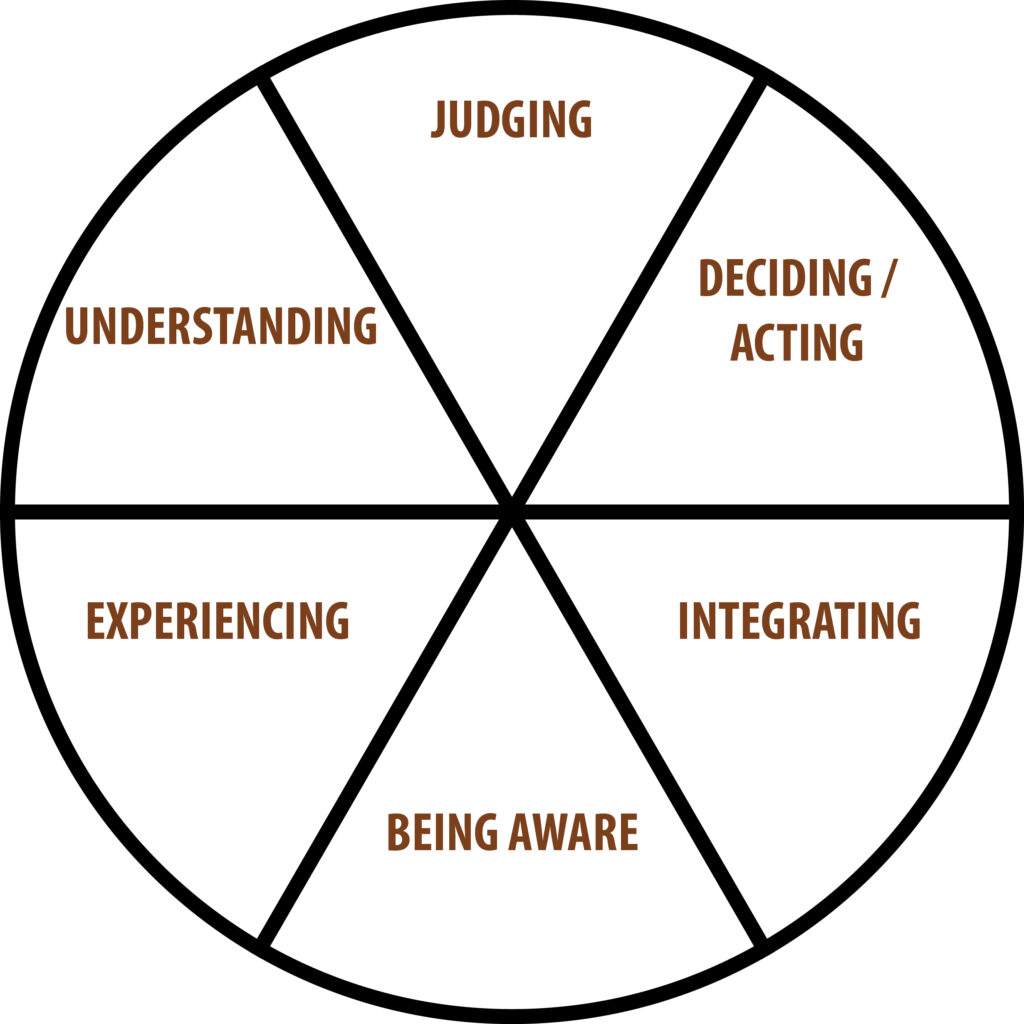

Nonetheless (fourth), knowing does generally (for the most part, for most individuals and collectives) take a certain “shape.” We have learned of the movement from doubt through inquiry into belief, from a state of dis-satisfaction into satisfaction. Often knowing takes this shape. It moves from a Being Aware of things to a more direct Experiencing things (sensation, perception). It moves from Experiencing to Understanding (doubt, inquiry), and into Judging (evaluation, confirmation, verification). Our knowing is then lived out through Deciding, Acting and Integrating, and then returns again to Being Aware, Experiencing, and so on, anew. Empirical discoveries, intuitive perceptions, rationalist analysis, pragmatic confirmations, and the like, all have their place. Sometimes, however, things do not follow this shape no neatly. Sometimes we discover things which break into our Understanding without much doubt. Sometimes we Act and through our actions Become Aware of things which only later we Understand. At times we jump to conclusions (Judging without Understanding), or we fail to look before we leap (Acting without Judging). But in general our knowing is a process that moves in a certain direction. (For a chart summarizing this process see Figure 9.1 The Stages of Human Knowing.)

Knowing begins where we are

Fifth, while our knowing has a certain shape, it has no absolute beginning point. Although Descartes’ rationalist “I think, therefore I am” has a good deal of respect in the history of philosophy East and West (and the same for Locke’s empiricism or Radhakrishnan’s intuitionism), there has simply been no consensus on a single, foundational “starting place” from which one can either begin or arbitrate our knowing. We must simply start from where we are (whether Experiencing, Understanding, Deciding or the like) and work our way out, correcting this or that aspect by means of the kinds of knowing and kinds of reality we are dealing with. Our knowing is inescapably, a knowing-in-the-world.

While individual knowledge is partial, community knowledge can be greater; only Infinite Mind is comprehensive

If knowledge begins where we are, is fallible, and takes a certain shape, then the process toward knowledge is ultimately a joining of minds in time. What this means then (sixth), is that while individual knowing may only be partial (yet often quite functional within a degree of practical life), community knowing is likely to be more reliable still. As you share your knowing with me, and as I welcome your knowing, permitting it to question mine, together we facilitate a greater range of operations, perspectives, justification and secure a greater likelihood of a fuller knowing. You can think of this in terms of a progression from individual knowing, through smaller and larger community knowing, perhaps ultimately to Infinite knowing.